| Latest Maths NCERT Books Solution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th |

Chapter 2 Lines and Angles

This section offers detailed solutions for the exercises presented in Chapter 2, "Lines and Angles", from the authoritative NCERT Class 6 Ganita Prakash textbook designated for the 2024-25 academic session. These solutions are meticulously prepared to support students as they embark on exploring fundamental geometric concepts, serving as an essential guide in understanding the basic elements that structure the visual world around us. The primary focus is on building a strong conceptual foundation regarding points, lines, line segments, rays, and the pivotal concept of angles.

Within these solutions, learners will find comprehensive walkthroughs demonstrating how to accurately identify these geometric entities within various diagrams and connect them to real-world scenarios. A substantial part is dedicated to the crucial skill of understanding, classifying, and working with different types of angles. Key classifications covered include:

- Acute Angles: Those measuring less than $90^\circ$.

- Obtuse Angles: Those measuring greater than $90^\circ$ but less than $180^\circ$.

- Right Angles: Precisely measuring $90^\circ$.

- Straight Angles: Forming a straight line and measuring exactly $180^\circ$.

- Reflex Angles: Angles greater than $180^\circ$ but less than $360^\circ$.

Furthermore, the solutions delve into the relationships between lines themselves. Students will gain clarity on identifying and differentiating between parallel lines (which never intersect), intersecting lines (which cross at a single point), and perpendicular lines (which intersect at a perfect right angle, $90^\circ$). Examples and methods for recognizing these configurations in diagrams are clearly illustrated. A critical aspect addressed is the understanding of relationships between angles formed by intersecting lines. This includes:

- Complementary Angles: Pairs of angles whose measures sum up to $90^\circ$, i.e., $m\angle A + m\angle B = 90^\circ$.

- Supplementary Angles: Pairs of angles whose measures sum up to $180^\circ$, i.e., $m\angle C + m\angle D = 180^\circ$.

- Adjacent Angles: Angles sharing a common vertex and a common side but no common interior points.

- Linear Pairs: Adjacent angles whose non-common sides form a straight line, making them supplementary.

- Vertically Opposite Angles: Angles formed opposite each other when two lines intersect; these are always equal in measure.

For problems that necessitate calculations – such as determining the measure of a complementary or supplementary angle to a given angle, or finding unknown angle measures in figures involving intersecting lines – the solutions provide explicit, step-by-step algebraic procedures. Often, this involves setting up and solving simple equations based on the geometric properties discussed. By diligently working through these explanations, students will enhance their ability to interpret geometric figures with precision, apply definitions accurately, and utilize fundamental angle properties as tools for problem-solving. This resource acts as a vital aid in developing foundational spatial reasoning and precision in geometric thinking, ensuring students solidify their understanding of the essential building blocks of geometry introduced in this chapter of the Class 6 Ganita Prakash (NCERT 2024-25) curriculum.

Figure it Out (Page 15 - 17)

Rihan marked a point on a piece of paper. How many lines can he draw that pass through the point?

Sheetal marked two points on a piece of paper. How many different lines can she draw that pass through both of the points?

Can you help Rihan and Sheetal find their answers?Answer:

Yes, we can help Rihan and Sheetal with their questions!

For Rihan's Question:

Rihan marked one point on a piece of paper.

Imagine that point is like the center of a big wheel. You can draw a spoke (a line) from the center to any point on the edge of the wheel. Since there are countless points on the edge, you can draw countless spokes.

Similarly, you can draw a line through the point in any direction you can think of - up-down, left-right, and all the diagonal directions in between.

Therefore, Rihan can draw an infinite or countless number of lines through a single point.

For Sheetal's Question:

Sheetal marked two points on a piece of paper.

Think about connecting these two dots with a straight ruler. There is only one exact way to place the ruler so that its edge touches both points at the same time. You cannot move or tilt the ruler and still have it touch both points.

This means there is only one unique straight line that can connect two distinct points.

Therefore, Sheetal can draw only one straight line that passes through both of her points.

Answer:

Looking at Figure 2.4, we can identify the different parts of the drawing.

Name the line segments in Fig. 2.4

A line segment is a part of a line that is bounded by two distinct end points. In the figure, the line segments are the straight pieces that connect the marked points.

The line segments are:

- LM (The segment between points L and M)

- MP (The segment between points M and P)

- PQ (The segment between points P and Q)

- QR (The segment between points Q and R)

Which of the five marked points are on exactly one of the line segments?

We need to find the points that are at the very beginning or end of the entire zigzag path, not in the middle where two segments meet.

The points on exactly one line segment are the endpoints of the entire path:

- Point L is an endpoint of only the segment LM.

- Point R is an endpoint of only the segment QR.

Which are on two of the line segments?

We need to find the points that act as a connection or a "corner" where two line segments meet.

The points on two line segments are:

- Point M is the endpoint of segment LM and also the endpoint of segment MP.

- Point P is the endpoint of segment MP and also the endpoint of segment PQ.

- Point Q is the endpoint of segment PQ and also the endpoint of segment QR.

Answer:

A ray is a part of a line that has a starting point but no endpoint. It extends infinitely in one direction. We name a ray by its starting point followed by another point on the ray.

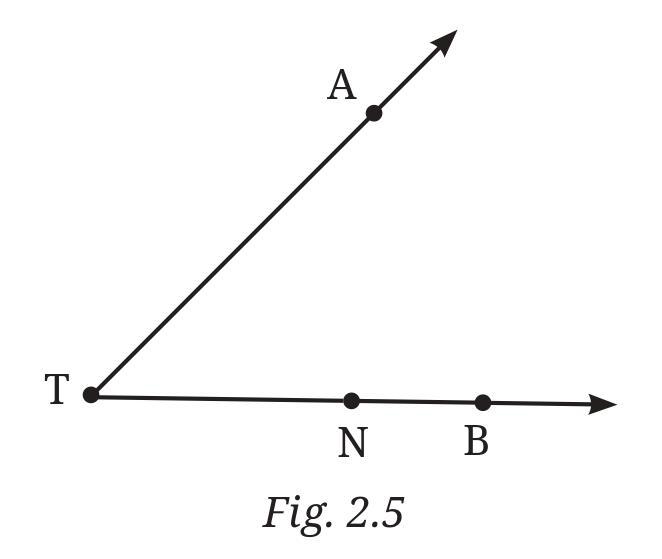

Name the rays shown in Fig. 2.5

Looking at the figure, we can see two lines originating from point T.

1. The ray that starts at T and goes upwards through point A is named Ray TA. We can also call it Ray TA, written as $\overrightarrow{TA}$.

2. The ray that starts at T and goes to the right through points N and B is named Ray TB or Ray TN. Since N and B are on the same ray starting from T, both names are correct. We can write it as $\overrightarrow{TB}$ or $\overrightarrow{TN}$.

Is T the starting point of each of these rays?

Yes, in the figure, both rays originate from the common point T. Point T is the vertex where the two rays meet.

Therefore, T is the starting point of both Ray TA and Ray TB.

a. $\overleftrightarrow{OP}$ and $\overleftrightarrow{OQ}$ meet at O.

b. $\overrightarrow{XY}$ and $\overleftrightarrow{PQ}$ intersect at point M.

c. Line $l$ contains points E and F but not point D.

d. Point P lies on AB.

Answer:

Here are the rough figures with appropriate labels for each of the given situations.

a. $\overleftrightarrow{OP}$ and $\overleftrightarrow{OQ}$ meet at O.

This describes two straight lines, line OP and line OQ, that intersect each other at the common point O.

b. $\overrightarrow{XY}$ and $\overleftrightarrow{PQ}$ intersect at point M.

This describes a ray XY (starting at X and going through Y) and a line PQ that cross each other at a single point labeled M.

c. Line $l$ contains points E and F but not point D.

This shows a straight line named $l$. The points E and F are located on the line, while the point D is located somewhere off the line.

d. Point P lies on line segment AB.

This shows a line segment with endpoints A and B. The point P is located somewhere between A and B on the segment.

a. Five points

b. A line

c. Four rays

d. Five line segments

Answer:

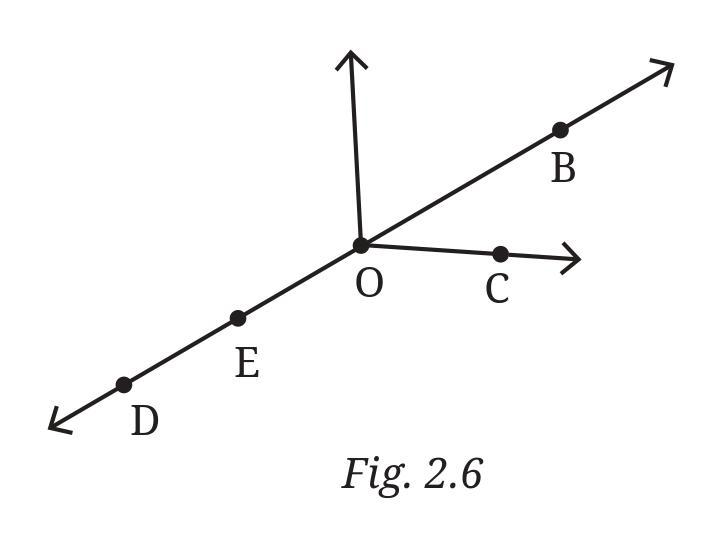

Based on the figure provided (Fig. 2.6), here are the answers with proper notation:

a. Five points

The five points that are clearly marked on the line are:

- D

- E

- O

- C

- B

b. A line

A line extends infinitely in both directions and is named by any two points on it. The line in the figure can be named:

- $\overleftrightarrow{DB}$ (Line DB)

(Other possible names include $\overleftrightarrow{DE}$, $\overleftrightarrow{OC}$, $\overleftrightarrow{EB}$, etc.)

c. Four rays

A ray has one starting point and extends infinitely in one direction. It is named with the starting point first.

- $\overrightarrow{OB}$ (This is the ray that starts at point O and extends infinitely to the right, passing through B).

- $\overrightarrow{OC}$ (This is also the ray that starts at point O and extends infinitely to the right, passing through C).

- $\overrightarrow{OD}$ (This is the ray that starts at point O and extends infinitely to the left, passing through D).

- $\overrightarrow{OE}$ (This is also the ray that starts at point O and extends infinitely to the left, passing through E).

d. Five line segments

A line segment is a part of a line with two fixed endpoints.

- $\overline{DE}$ (The segment between D and E)

- $\overline{EO}$ (The segment between E and O)

- $\overline{OC}$ (The segment between O and C)

- $\overline{CB}$ (The segment between C and B)

- $\overline{OB}$ (The segment between O and B)

a. Can you also name it as $\overrightarrow{OB}$ ? Why?

b. Can we write $\overrightarrow{OA}$ as $\overrightarrow{AO}$ ? Why or why not?

Answer:

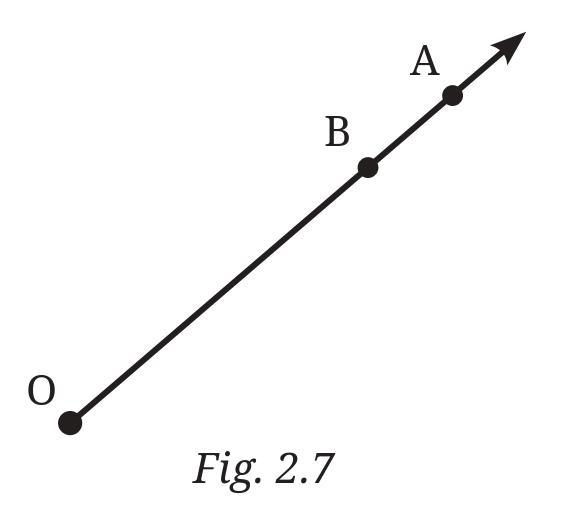

This question is about how we name rays and what the name tells us about the ray.

a. Can you also name it as $\overrightarrow{OB}$? Why?

Yes, we can also name the ray as $\overrightarrow{OB}$.

Why: A ray is defined by its starting point and its direction. To name a ray, we use its starting point first, followed by any other point that lies on the ray. In Figure 2.7:

- The ray starts at point O.

- It extends in the direction that passes through point A and point B.

Since both $\overrightarrow{OA}$ and $\overrightarrow{OB}$ describe the exact same ray (starting at O and going in the same direction), they are just two different names for the same ray.

b. Can we write $\overrightarrow{OA}$ as $\overrightarrow{AO}$? Why or why not?

No, we cannot write $\overrightarrow{OA}$ as $\overrightarrow{AO}$.

Why not: The order of the letters in a ray's name is very important. The first letter always indicates the starting point of the ray.

- $\overrightarrow{OA}$ means the ray starts at point O and goes on forever in the direction of point A.

- $\overrightarrow{AO}$ would mean a completely different ray that starts at point A and goes on forever in the direction of point O.

Since they have different starting points and go in opposite directions, $\overrightarrow{OA}$ and $\overrightarrow{AO}$ are not the same ray.

Intext Question (Page 17 - 18)

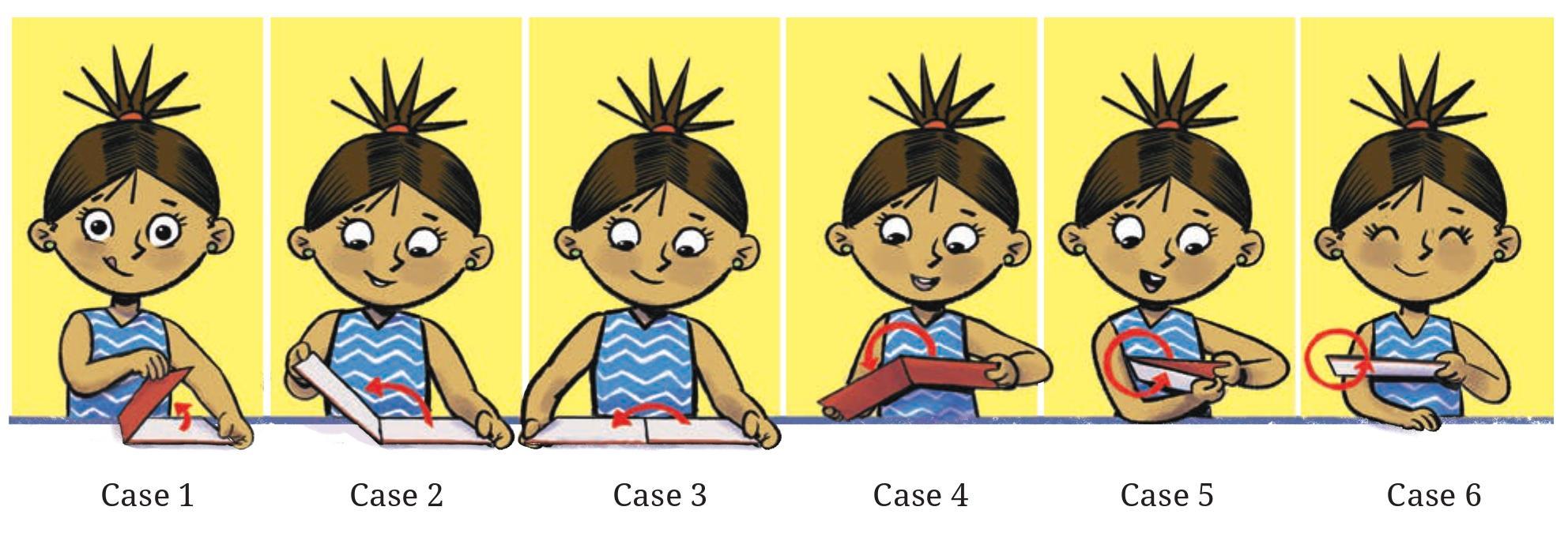

Vidya has just opened her book. Let us observe her opening the cover of the book in different scenarios.

Question: Do you see angles being made in each of these cases? Can you mark their arms and vertex?

Answer:

Yes, we can see angles being made in each of the cases as Vidya opens her book. An angle is formed by two rays that share a common starting point, called the vertex.

In this situation:

- The vertex of the angle is the spine of the book.

- One arm of the angle is the surface of the rest of the book lying flat.

- The other arm of the angle is the front cover.

As Vidya opens the cover, the angle between the cover and the rest of the book changes.

Here is a correct description for each case:

Case 1: The book is slightly open. A small angle that is less than 90° is formed. This is an acute angle.

Case 2: Vidya opens the cover wider. The angle is now greater than 90° but less than 180°. This is an obtuse angle.

Case 3: The book is opened completely flat. The cover and the rest of the book form a straight line. This is a straight angle ($180^\circ$).

Case 4: Vidya starts to fold the cover underneath the book. The angle formed between the cover and the flat part of the book is now greater than $180^\circ$. This is a reflex angle.

Case 5: The cover is folded further underneath. It is still a reflex angle, but it is getting larger as it approaches a full circle.

Case 6: The cover is folded all the way around so it touches the back of the book. The angle has made a full circle. This is a complete angle ($360^\circ$).

Figure it Out (Page 19 - 21)

Answer:

Yes, we can find many angles in all of the given pictures. Angles are formed everywhere around us where lines or edges meet.

Finding Angles in the Pictures:

- Bicycle: The frame of the bicycle has several angles where the tubes connect. For example, there are angles at points A, B, C, and D. The spokes of the wheels also form many small angles at the center hub.

- Crate: The wooden slats are arranged in a pattern that creates many angles where they cross each other. Also, the four corners of the crate itself form right angles ($90^\circ$).

- Ladder: The open step-ladder forms an angle at the top where the two sides are hinged together. The steps and the legs of the ladder also form many angles.

- Bridge: The support structure of the bridge is made of many triangles. Every triangle has three angles inside it.

Drawing and Naming an Angle at D:

Let's choose the angle formed at point D on the bicycle to illustrate.

- The angle we have chosen is $\angle CDA$ (or $\angle ADC$).

- The vertex of this angle is the point where the two arms meet, which is point D.

- The two rays (or arms) that form this angle are Ray DC (written as $\overrightarrow{DC}$) and Ray DA (written as $\overrightarrow{DA}$).

Question 2. Draw and label an angle with arms ST and SR.

Answer:

Here is a drawing of an angle with arms ST and SR, along with its labels.

Explanation of the drawing:

- The two arms of the angle are Ray ST (written as $\overrightarrow{ST}$) and Ray SR (written as $\overrightarrow{SR}$).

- The common starting point for both rays is S. This point is the vertex of the angle.

- Point T lies on one arm, and point R lies on the other arm.

This angle can be named as $\angle TSR$ or $\angle RST$. It is important that the letter for the vertex (S) is always in the middle when naming the angle with three letters.

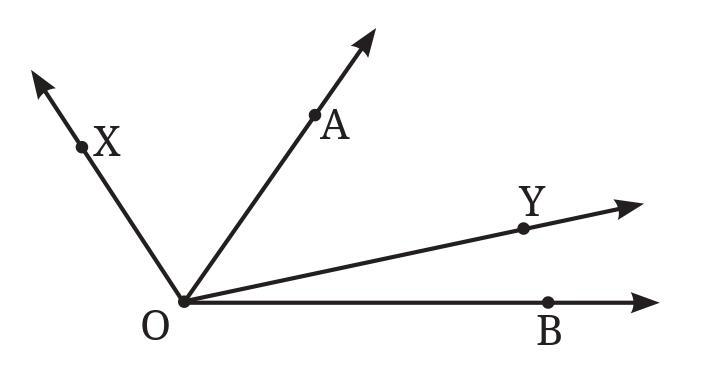

Answer:

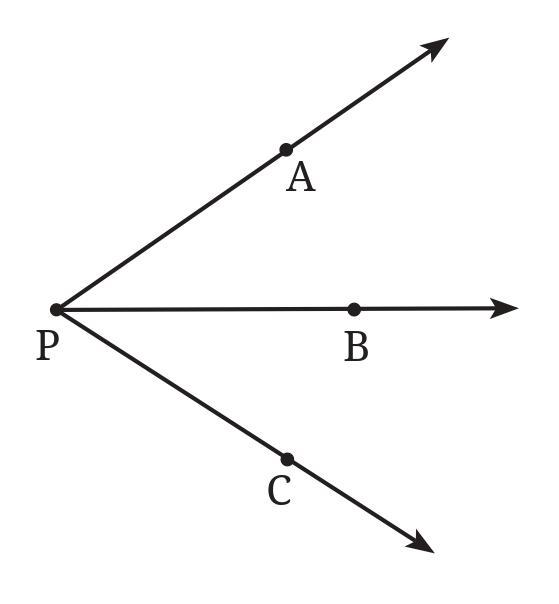

In the given figure, we see three rays originating from the common point P: $\overrightarrow{PA}$, $\overrightarrow{PB}$, and $\overrightarrow{PC}$.

The label ∠APC specifically refers to the angle formed by the ray $\overrightarrow{PA}$ and the ray $\overrightarrow{PC}$.

We cannot label ∠APC as simply ∠P because the point P is the vertex for more than one angle in the figure. Using the single letter ∠P would be ambiguous and confusing because it is not clear which angle we are talking about.

At vertex P, there are three distinct angles:

- ∠APB (the angle between ray PA and ray PB)

- ∠BPC (the angle between ray PB and ray PC)

- ∠APC (the angle between ray PA and ray PC)

If someone says "look at angle P", we would not know which of these three angles they mean.

Therefore, to avoid confusion, we must use three letters to name the angle, with the vertex letter (P) always in the middle. This clearly identifies the two rays that form the specific angle we are referring to.

Answer:

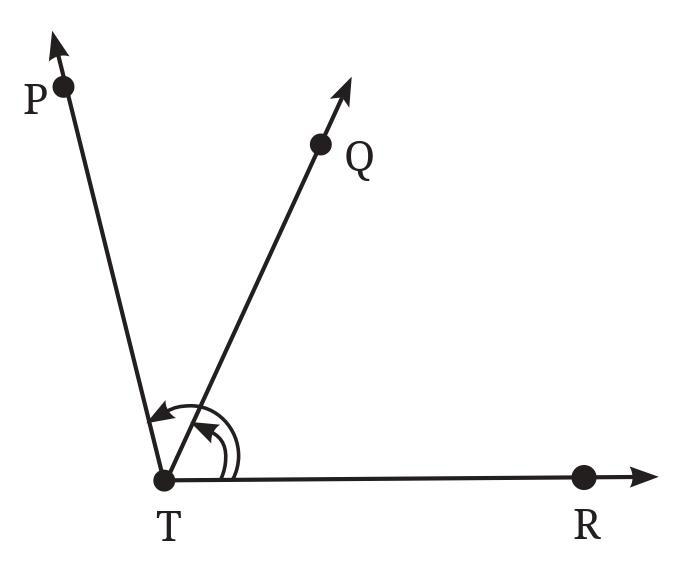

In the given figure, there are three rays originating from the common vertex T: $\overrightarrow{TP}$, $\overrightarrow{TQ}$, and $\overrightarrow{TR}$.

The arcs with arrows in the figure indicate which angles we need to name.

There are two angles marked:

1. The smaller angle formed by the rays $\overrightarrow{TR}$ and $\overrightarrow{TQ}$.

2. The larger angle formed by the rays $\overrightarrow{TR}$ and $\overrightarrow{TP}$.

Here are the names for the marked angles:

- The smaller angle can be named as ∠RTQ or ∠QTR.

- The larger angle can be named as ∠RTP or ∠PTR.

Note: We can also see a third, unmarked angle, which is ∠PTQ. The two marked angles, ∠RTQ and ∠PTQ, together make up the largest marked angle, ∠RTP.

So, $\angle RTQ + \angle QTP = \angle RTP$.

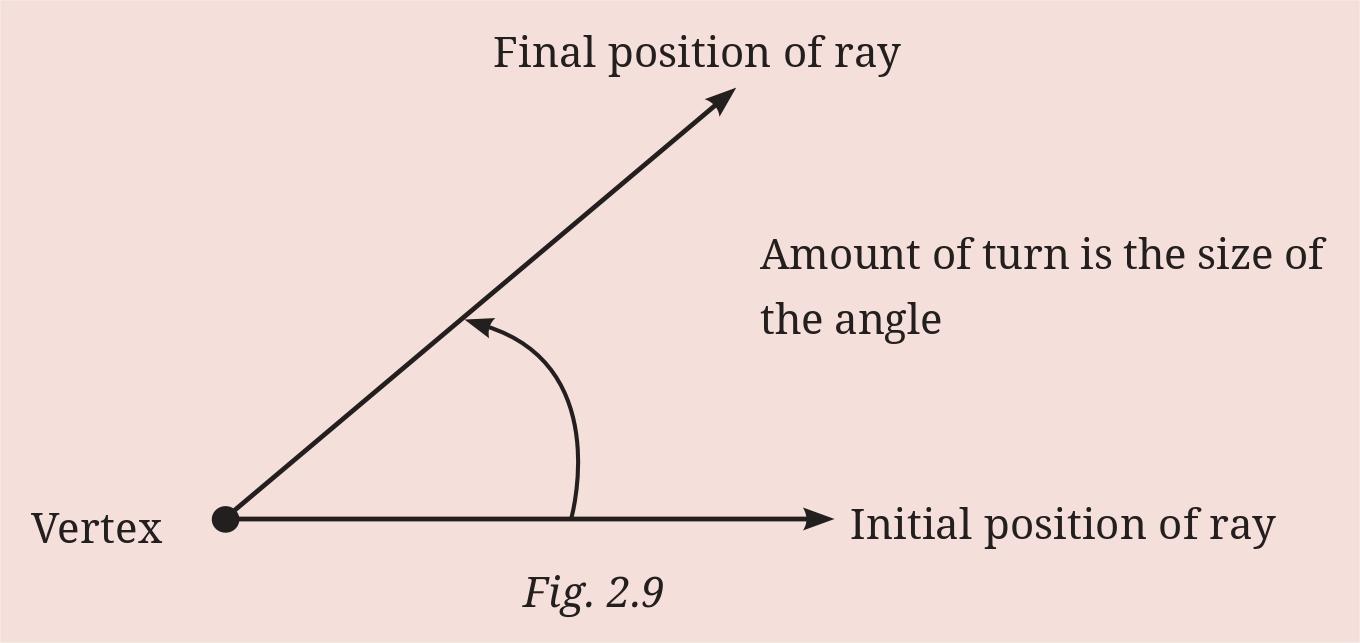

Question 5. Mark any three points on your paper that are not on one line. Label them A, B, C. Draw all possible lines going through pairs of these points. How many lines do you get? Name them. How many angles can you name using A, B, C? Write them down, and mark each of them with a curve as in Fig. 2.9.

Answer:

Let's follow the steps to create the figure and answer the questions.

First, we mark three points A, B, and C that are not in a single straight line. Then, we draw the lines that pass through each pair of these points.

How many lines do you get? Name them.

By connecting each pair of points, we get 3 lines. The names of these lines are:

- Line AB (written as $\overleftrightarrow{AB}$)

- Line BC (written as $\overleftrightarrow{BC}$)

- Line AC (written as $\overleftrightarrow{AC}$)

How many angles can you name? Write them down, and mark them.

Since the three points form a triangle, there is an angle at each of the three vertices (A, B, and C). So, we can name 3 angles.

The names of the angles are:

- $\angle BAC$ (or $\angle CAB$)

- $\angle ABC$ (or $\angle CBA$)

- $\angle BCA$ (or $\angle ACB$)

In the drawing above, each of these angles is marked with a curved arc, just like the "Amount of turn" is marked in Fig. 2.9. This curve shows the opening or turn between the two arms of the angle at its vertex.

Question 6. Now mark any four points on your paper so that no three of them are on one line. Label them A, B, C, D. Draw all possible lines going through pairs of these points. How many lines do you get? Name them. How many angles can you name using A, B, C, D? Write them all down, and mark each of them with a curve as in Fig. 2.9.

Answer:

Let's follow the steps for four points, where no three points are on the same line.

How many lines do you get?

You can draw a line between each unique pair of points. The pairs are:

(A, B), (A, C), (A, D), (B, C), (B, D), (C, D)

You get 6 lines.

Name the lines:

The names of the six lines are:

- Line AB ($\overleftrightarrow{AB}$)

- Line AC ($\overleftrightarrow{AC}$)

- Line AD ($\overleftrightarrow{AD}$)

- Line BC ($\overleftrightarrow{BC}$)

- Line BD ($\overleftrightarrow{BD}$)

- Line CD ($\overleftrightarrow{CD}$)

How many angles can you name using A, B, C, D?

At each of the four points, you can form three different angles using the lines that connect to it.

- At vertex A: $\angle BAC$, $\angle BAD$, $\angle CAD$ (3 angles)

- At vertex B: $\angle ABC$, $\angle ABD$, $\angle CBD$ (3 angles)

- At vertex C: $\angle BCA$, $\angle BCD$, $\angle ACD$ (3 angles)

- At vertex D: $\angle CDA$, $\angle CDB$, $\angle ADB$ (3 angles)

The total number of angles is $3 + 3 + 3 + 3 = 12$.

You can name 12 angles.

Write them all down:

The twelve angles are:

- $\angle BAC$, $\angle BAD$, $\angle CAD$

- $\angle ABC$, $\angle ABD$, $\angle CBD$

- $\angle BCA$, $\angle BCD$, $\angle ACD$

- $\angle CDA$, $\angle CDB$, $\angle ADB$

As shown in the drawing, each of these angles would be marked with a curve at its respective vertex.

Figure it Out (Page 23)

Answer:

This is a fun activity to explore angles by folding paper!

Part 1: Angles formed by one fold

When you fold a rectangular sheet of paper and draw a line along the crease, that line will intersect with the straight edges (sides) of the paper, forming several angles.

Let's look at the angles where the fold meets the top edge of the paper. Two angles are formed there. Let's call them Angle A and Angle B.

Similarly, where the fold meets the bottom edge, two more angles are formed. Let's call them Angle C and Angle D.

Comparison of Angles:

- Angle A and Angle B add up to a straight angle ($180^\circ$) because they lie on the straight top edge of the paper.

- Angle C and Angle D also add up to a straight angle ($180^\circ$).

- Because the top and bottom edges of the rectangle are parallel, the angles are related. Angle A is equal to Angle D (alternate interior angles). Similarly, Angle B is equal to Angle C.

Part 2: Making different angles by folding

You can make many different types of angles by folding a rectangular sheet of paper.

1. Making a Right Angle ($90^\circ$):

Take one edge of the paper and fold it over so that it lies perfectly along itself. The crease you make will be exactly perpendicular to that edge, forming a perfect right angle.

2. Making an Acute Angle (less than $90^\circ$):

Fold any corner of the paper over, but not completely flat. The angle formed at the corner of the fold will be an acute angle.

3. Making an Obtuse Angle (greater than $90^\circ$):

Start with a right angle (one of the corners of the paper). Then, make a diagonal fold that starts from the corner but goes outwards, making the corner angle appear wider. The new angle formed by the crease and one of the edges will be an obtuse angle.

Largest and Smallest Angle You Made

- The smallest angle you can make is an acute angle. By making a very sharp fold, you can create an angle that is very close to $0^\circ$.

- The largest angle you can easily make with a single fold across the paper is a straight angle ($180^\circ$) by just drawing a straight line across it. If you consider the angle on the "outside" of a fold, you can also create reflex angles (greater than $180^\circ$). By folding the paper almost completely back on itself, you can create a reflex angle that is very close to a complete angle ($360^\circ$).

By comparing the angles you've made, you will notice that acute angles are "sharper" or more "pointed" than right angles, and obtuse angles are "wider" than right angles.

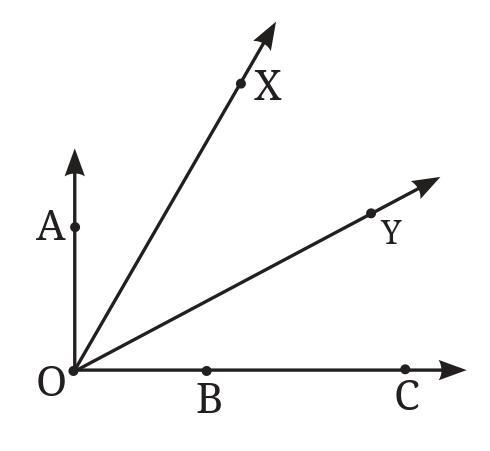

a. ∠AOB or ∠XOY

b. ∠AOB or ∠XOB

c. ∠XOB or ∠XOC

Discuss with your friends on how you decided which one is greater.

Answer:

To compare angles, we look at the amount of "opening" or "turn" between their arms. The length of the arms does not change the size of the angle.

a. ∠AOB or ∠XOY

Answer: ∠AOB is greater than ∠XOY.

Why: The opening between the arms $\overrightarrow{OA}$ and $\overrightarrow{OB}$ is wider than the opening between the arms $\overrightarrow{OX}$ and $\overrightarrow{OY}$.

b. ∠AOB or ∠XOB

Answer: ∠AOB is greater than ∠XOB.

Why: Both angles share the same arm $\overrightarrow{OB}$. Since the arm $\overrightarrow{OX}$ is inside the angle ∠AOB, the angle ∠AOB has a wider opening.

c. ∠XOB or ∠XOC

Answer: ∠XOB is equal to ∠XOC.

Why: Both angles share the arm $\overrightarrow{OX}$. Their other arms, $\overrightarrow{OB}$ and $\overrightarrow{OC}$, are the exact same ray because points B and C lie on the same straight line starting from O. Since the angles are formed by the same pair of rays, they are equal in size.

Discussion with your friends:

You can decide which angle is greater by tracing them or imagining them on top of each other. If one angle fits completely inside another (sharing the same vertex), the outer one is larger. If two angles are formed by the exact same pair of rays, they are equal, no matter which points are used to name them.

Answer:

∠XOY is greater than ∠AOB.

Reason:

The size of an angle is determined by the amount of "opening" or "turn" between its two arms, not by how long the arms are drawn.

By visually comparing the two angles in the figure, the opening between the rays $\overrightarrow{OX}$ and $\overrightarrow{OY}$ is clearly wider than the opening between the rays $\overrightarrow{OA}$ and $\overrightarrow{OB}$. Therefore, ∠XOY is the greater angle.

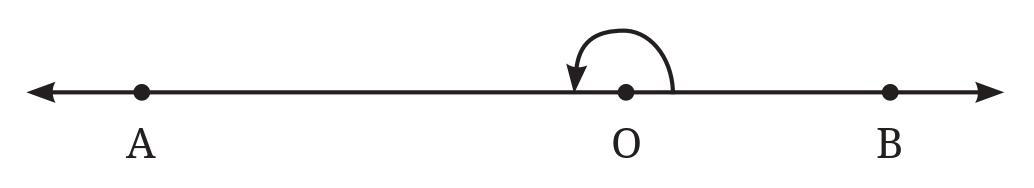

Intext Question (Page 28)

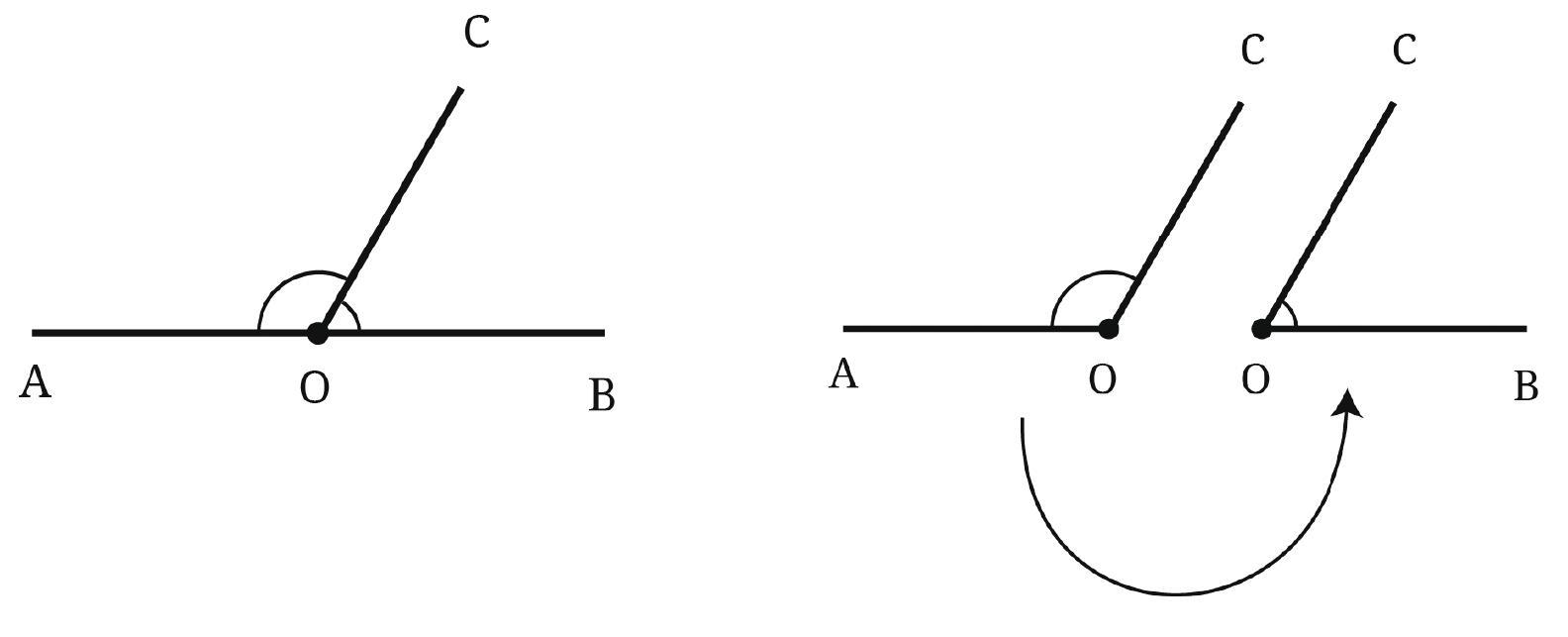

Let us consider a straight angle ∠AOB. Observe that any ray $\overrightarrow{OC}$ divides it into two angles, ∠AOC and ∠COB.

Question: Is it possible to draw $\overrightarrow{OC}$ such that the two angles are equal to each other in size?

Answer:

Yes, it is possible to draw the ray $\overrightarrow{OC}$ such that the two angles, ∠AOC and ∠COB, are equal to each other in size.

Here is the explanation:

1. The angle ∠AOB is a straight angle. A straight angle always measures $180^\circ$.

2. The ray $\overrightarrow{OC}$ divides the straight angle ∠AOB into two adjacent angles, ∠AOC and ∠COB. This means that their sizes add up to the total size of the straight angle:

$\angle AOC + \angle COB = \angle AOB = 180^\circ$

3. If we want the two angles to be equal in size, then each angle must be exactly half of the total $180^\circ$.

Size of each angle = $\frac{180^\circ}{2} = 90^\circ$

4. An angle that measures exactly $90^\circ$ is called a right angle.

5. To make this happen, the ray $\overrightarrow{OC}$ must be drawn perpendicular (standing straight up or down) to the line $\overleftrightarrow{AB}$ at point O.

Here is a picture of what it would look like:

In this case, both ∠AOC and ∠COB are right angles, and they are equal to each other.

Figure it Out (Page 29 - 31)

Question 1. How many right angles do the windows of your classroom contain? Do you see other right angles in your classroom?

Answer:

The number of right angles in the windows and other objects in a classroom can be determined by observing their shapes. A right angle is an angle that measures exactly $90^\circ$, commonly found at the corners of rectangular and square objects.

1. Right Angles in Classroom Windows

Most classroom windows are rectangular in shape.

A rectangle has four corners, and each corner is a right angle ($90^\circ$).

Therefore, a single rectangular window contains 4 right angles.

If a classroom has 'n' rectangular windows, the total number of right angles in the windows would be $4 \times n$. For example, if a classroom has 3 windows, it would have $4 \times 3 = 12$ right angles from the windows.

2. Other Right Angles in the Classroom

Yes, there are numerous other examples of right angles in a typical classroom. A right angle is formed wherever two straight lines or flat surfaces meet perpendicularly. Some common examples include:

- The corners of the blackboard or whiteboard.

- The corners of a book, a notebook, or a sheet of paper.

- The corners of the top surface of a desk or a table.

- The corners of the classroom door and its frame.

- The corners where two adjacent walls meet each other.

- The corners where the walls meet the floor and the ceiling.

- The corners of a computer monitor or a duster.

- The angle in a set square in a geometry box that measures $90^\circ$.

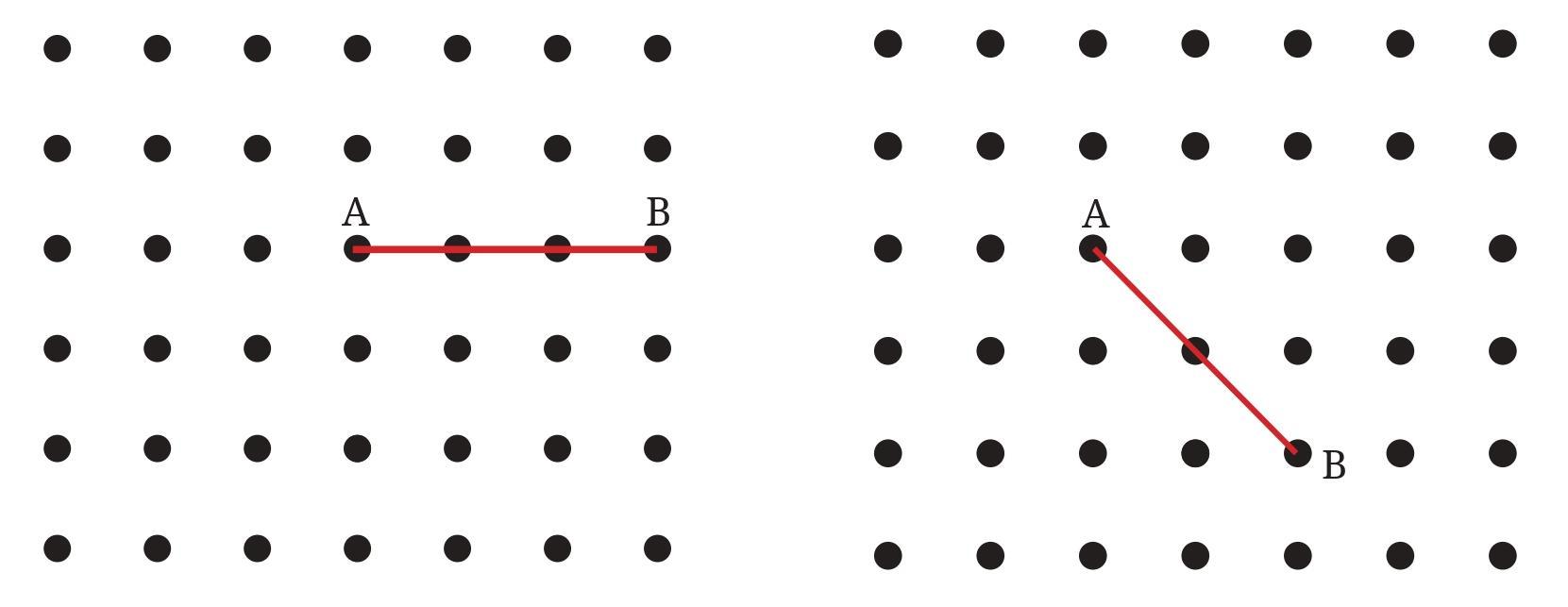

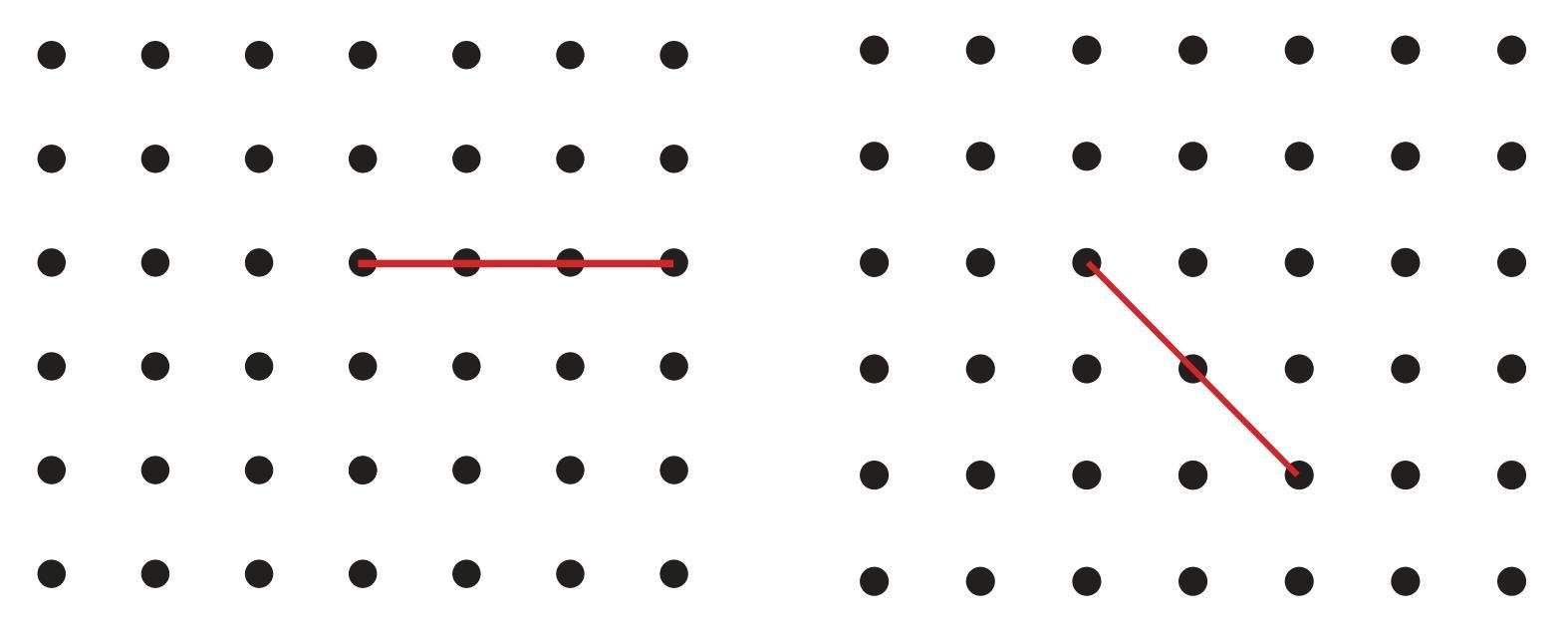

Answer:

A straight angle is an angle that measures exactly $180^\circ$. It looks like a straight line. To create a straight angle at point A on the grid, we need to draw a straight line that passes through point A and connects at least one point on one side of A with another point on the opposite side of A.

There are several ways to do this by joining A to other grid points. The different ways are shown below:

1. Horizontal Line

We can draw a horizontal line that passes through point A and all the other points in the same row. This forms a straight angle at A.

2. Vertical Line

We can draw a vertical line that passes through point A and all the other points in the same column. This also forms a straight angle at A.

3. Diagonal Line (Bottom-Left to Top-Right)

A straight angle can be formed by drawing a diagonal line that passes through A, connecting points from the bottom-left to the top-right of the grid.

4. Diagonal Line (Top-Left to Bottom-Right)

Another straight angle can be formed by drawing a diagonal line that passes through A, connecting points from the top-left to the bottom-right of the grid.

5. Steep Diagonal Line (Upwards)

A straight angle can also be formed along a steeper diagonal. This line connects A with a point that is one unit to the left and two units down, and another point that is one unit to the right and two units up.

6. Steep Diagonal Line (Downwards)

Similarly, a straight angle can be formed along another steep diagonal. This line connects A with a point that is one unit to the left and two units up, and another point that is one unit to the right and two units down.

In total, there are six different ways to draw a line through point A and at least two other grid points to form a straight angle at A.

Hint: Extend the line further as shown in the figure below. To get a right angle at A, we need to draw a line through it that divides the straight angle CAB into two equal parts.

Answer:

A right angle is an angle that measures exactly $90^\circ$. To form a right angle at point A on the grid, we need to draw two lines from A to other grid points such that the two lines are perpendicular to each other.

As hinted, a right angle is half of a straight angle ($180^\circ$). This means if we have a straight line passing through A, any line that is perpendicular to it will form a right angle with it at point A.

There are four distinct ways to form a right angle at point A by connecting it to other points on the grid.

Way 1: Horizontal and Vertical Lines

The most straightforward way to create a right angle is by using a horizontal line and a vertical line. We can draw one line connecting the points in the same row as A, and a second line connecting the points in the same column as A. These two lines intersect at A to form a perfect right angle.

Way 2: Main Diagonal Lines

A right angle can be formed by two perpendicular diagonal lines. One line runs from top-left to bottom-right through A. The second line runs from top-right to bottom-left through A. These diagonals have slopes that are negative reciprocals of each other, making them perpendicular.

Way 3: 'Knight's Move' Diagonals (2 steps across, 1 step down)

We can form right angles using steeper diagonals, similar to a "knight's move" in chess. One line connects points by moving 2 units horizontally and 1 unit vertically. The line perpendicular to it connects points by moving 1 unit horizontally and 2 units vertically in the perpendicular direction.

Way 4: 'Knight's Move' Diagonals (1 step across, 2 steps down)

This is the reverse of the previous case. One line connects points by moving 1 unit horizontally and 2 units vertically. The perpendicular line connects points by moving 2 units horizontally and 1 unit vertically in the perpendicular direction.

(a) How many right angles do you have now? Justify why the angles are exact right angles.

(b) Describe how you folded the paper so that any other person who doesn’t know the process can simply follow your description to get the right angle.

Answer:

(a) How many right angles do you have now? Justify why the angles are exact right angles.

When a second crease is made perpendicular to the first slanting crease, the two creases will intersect. At the point of intersection, four right angles are formed.

Justification:

The first crease on the paper represents a straight line. A straight line forms a straight angle, which measures $180^\circ$.

The process of creating the second crease involves folding the first crease exactly onto itself. When you do this, you are essentially dividing the straight angle ($180^\circ$) of the first crease into two equal parts. This process is known as bisecting the angle.

Therefore, each of the two adjacent angles formed by the new crease is half of the straight angle:

$\frac{180^\circ}{2} = 90^\circ$

Since these two adjacent angles are $90^\circ$, they are right angles. The angles opposite to them (vertically opposite angles) are also equal, which means all four angles formed at the intersection of the two creases are exact right angles.

(b) Describe how you folded the paper so that any other person who doesn’t know the process can simply follow your description to get the right angle.

Here is a simple, step-by-step description of how to fold a paper to create a right angle:

Step 1: Take a sheet of paper (any shape will work).

Step 2: Make a single fold anywhere on the paper to create a slanting crease. Press it firmly to make the line clear. Then, unfold the paper. This line is your first crease (let's call it Crease 1).

Step 3: Now, fold the paper again. This time, your goal is to make the line of Crease 1 fold back perfectly onto itself. Align one part of Crease 1 exactly on top of the other part of Crease 1.

Step 4: While holding Crease 1 in alignment, press the paper down to create a new, second fold. This is your Crease 2.

Step 5: Unfold the paper completely. You will now see two creases intersecting. The two creases are perpendicular to each other, and the four angles formed where they cross are all right angles ($90^\circ$).

Figure it Out (Page 31 - 32)

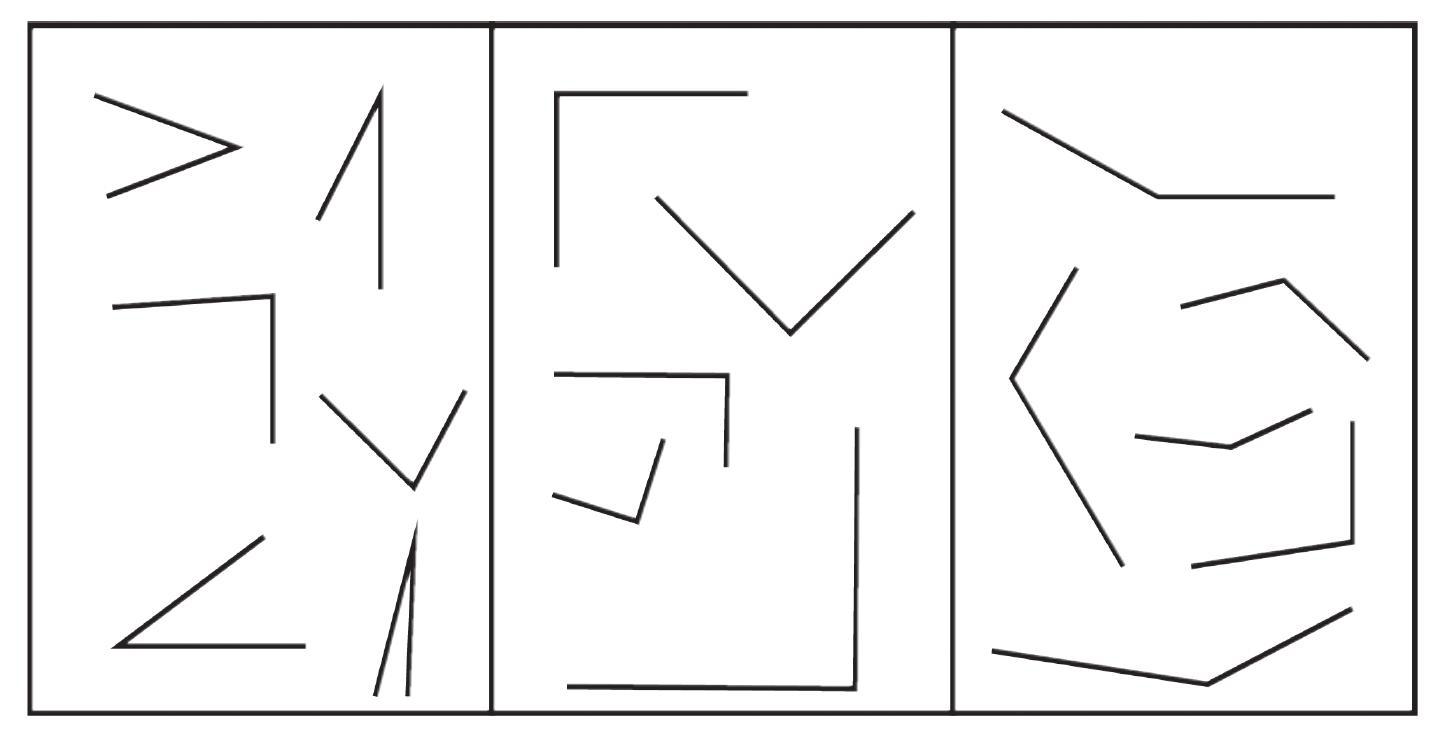

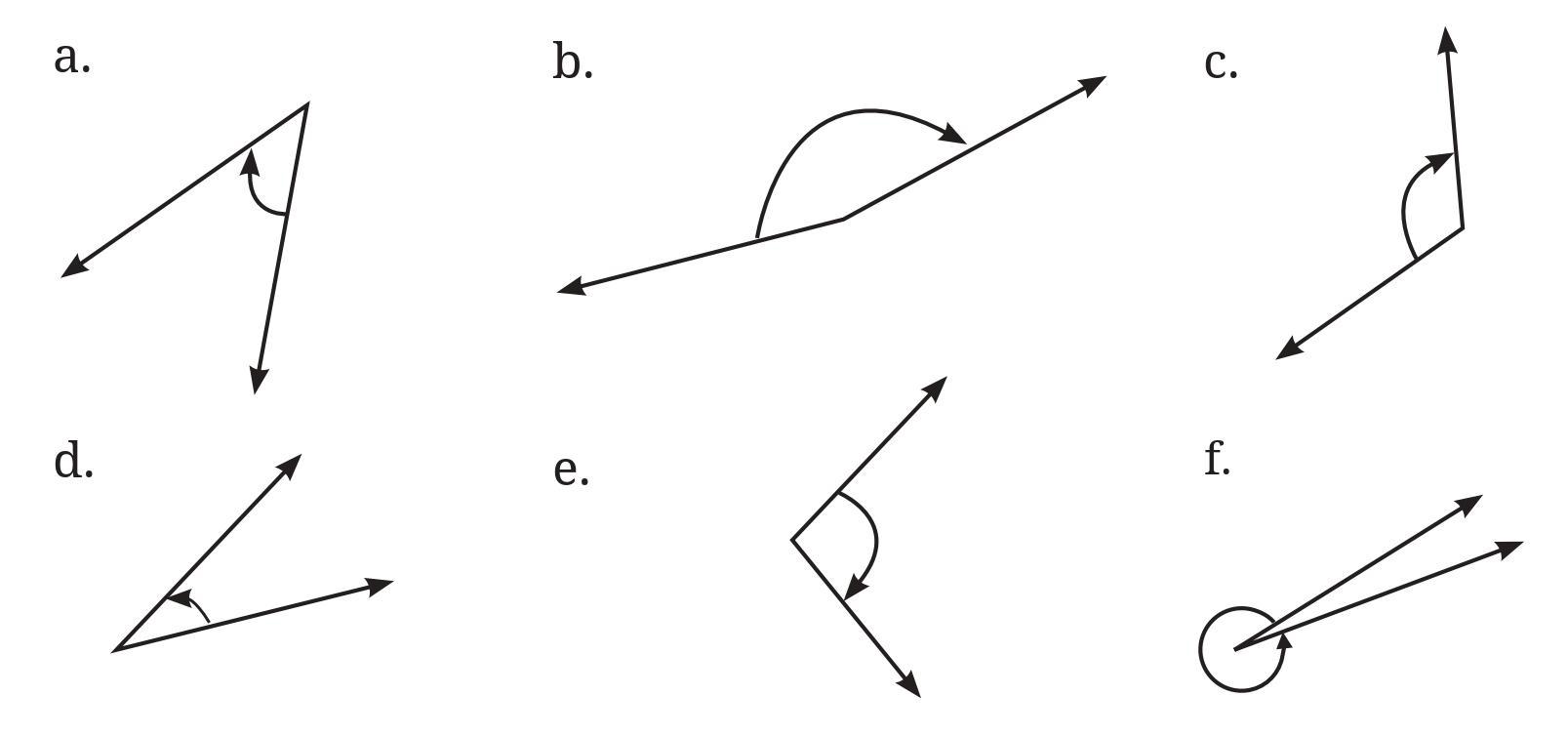

Question 1. Identify acute, right, obtuse and straight angles in the previous figures.

Answer:

By observing the figures in the three panels, we can identify and count the acute, right, and obtuse angles as requested.

- Acute Angle: An angle whose measure is less than $90^\circ$.

- Right Angle: An angle whose measure is exactly $90^\circ$.

- Obtuse Angle: An angle whose measure is greater than $90^\circ$ but less than $180^\circ$.

Left Panel: 6 Acute Angles

This panel contains 6 acute angles. These are the angles that are "sharper" or smaller than a right angle. Each of the six corners formed by the lines in this box is an acute angle.

Middle Panel: 5 Right Angles

This panel contains 5 right angles. These angles measure exactly $90^\circ$ and form perfect 'L' shapes. You can find five such corners within this box.

Right Panel: 6 Obtuse Angles

This panel contains 6 obtuse angles. These are the angles that are "wider" or larger than a right angle. All six corners formed by the lines in this box are obtuse angles.

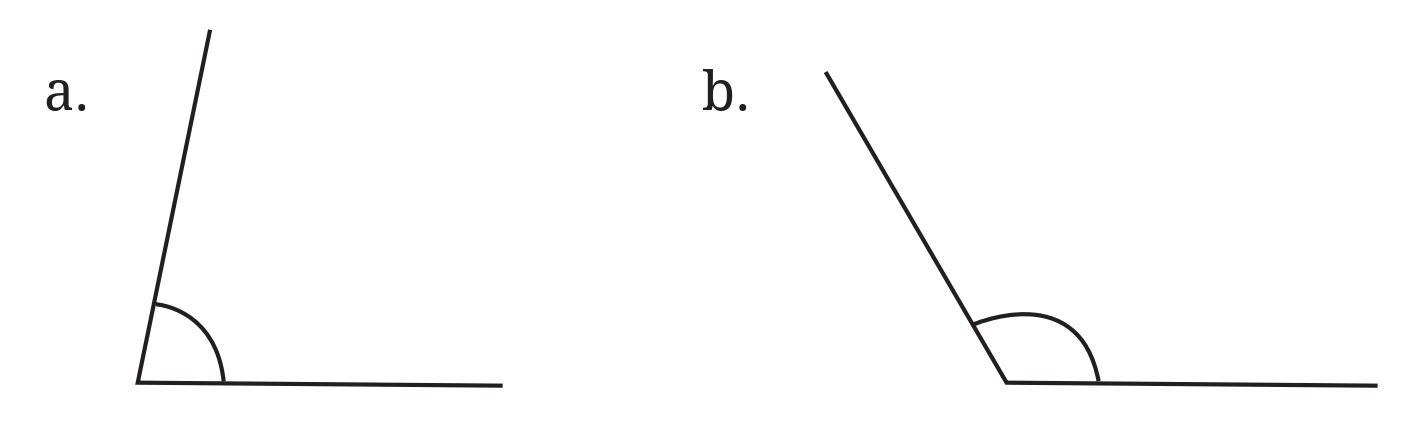

Question 2. Make a few acute angles and a few obtuse angles. Draw them in different orientations.

Answer:

An angle is a figure formed by two rays, called the sides of the angle, sharing a common endpoint, called the vertex of the angle. Angles can be classified based on their measures.

Acute Angles

An acute angle is an angle whose measure is greater than $0^\circ$ and less than $90^\circ$. They are "sharper" or smaller than a right angle.

Here are a few examples of acute angles drawn in different orientations:

Obtuse Angles

An obtuse angle is an angle whose measure is greater than $90^\circ$ and less than $180^\circ$. They are "wider" or larger than a right angle but not a straight line.

Here are a few examples of obtuse angles drawn in different orientations:

Question 3. Do you know what the words acute and obtuse mean? Acute means sharp and obtuse means blunt. Why do you think these words have been chosen?

Answer:

Yes, the words "acute" and "obtuse" were chosen for angles precisely because of their literal meanings, which describe the physical appearance of the angles themselves.

Why "Acute" is used for Angles less than $90^\circ$

The word acute comes from the Latin word 'acutus', which means "sharp" or "pointed".

An acute angle, which measures less than $90^\circ$, forms a shape that looks like a sharp point. Think of the tip of a needle, an arrowhead, or a sharp thorn. These objects have a very small, pointed angle at their tip, which allows them to pierce things easily. Because the angle itself looks sharp, the word "acute" is a fitting description.

Why "Obtuse" is used for Angles greater than $90^\circ$

The word obtuse comes from the Latin word 'obtusus', which means "blunt" or "dull".

An obtuse angle, which measures more than $90^\circ$ but less than $180^\circ$, forms a wide, open shape. It does not have a sharp point; instead, its corner looks rounded or blunt. Think of a corner that is not sharp enough to be dangerous, or a tool that has become dull. Because the angle is wide and not pointed, the word "obtuse" is a very appropriate name for it.

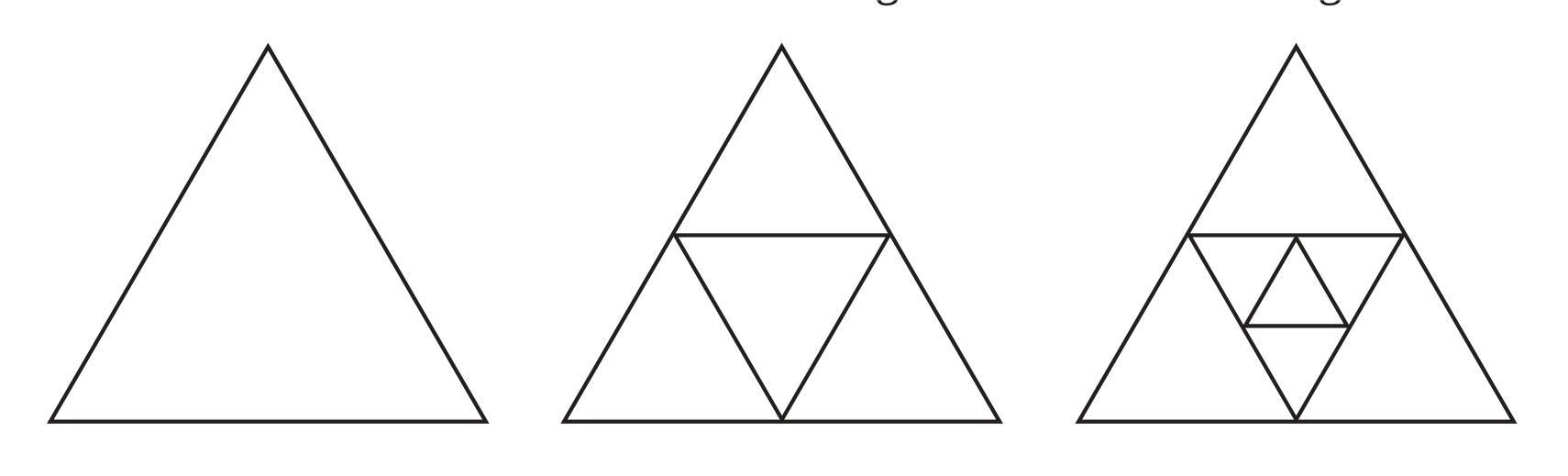

What will be the next figure and how many acute angles will it have? Do you notice any pattern in the numbers?

Answer:

To find the number of acute angles in each figure, we will assume that the largest triangle is an equilateral triangle, and each subsequent division is made by connecting the midpoints of the sides. This means all the triangles formed are equilateral, and all their internal angles are $60^\circ$, which is an acute angle.

Number of Acute Angles in Figure 1

The first figure is a single triangle. An equilateral triangle has 3 vertices, and each vertex has one acute angle ($60^\circ$).

Number of acute angles = 3

Number of Acute Angles in Figure 2

This figure is divided into 4 smaller equilateral triangles. We can count the angles at each vertex:

- There are 3 outer vertices (the corners of the large triangle). Each has 1 acute angle. (3 angles)

- There are 3 inner vertices (where the corners of the central triangle meet). At each of these points, 3 smaller triangles meet, forming 3 acute angles. (3 vertices $\times$ 3 angles/vertex = 9 angles)

Total number of acute angles = $3 + 9 = 12$

Number of acute angles = 12

Number of Acute Angles in Figure 3

This figure takes Figure 2 and subdivides its central triangle into 4 even smaller triangles. This process adds 9 new acute angles to the previous total.

Total number of acute angles = (Angles in Figure 2) + 9 = $12 + 9 = 21$

Number of acute angles = 21

The Next Figure and its Acute Angles

The pattern involves taking the innermost, central, downward-pointing triangle and subdividing it into four smaller triangles. Therefore, the next figure (Figure 4) will look like Figure 3, but with the smallest central triangle also subdivided.

Following the pattern, this new subdivision will add another 9 acute angles.

Number of acute angles in the next figure = (Angles in Figure 3) + 9 = $21 + 9 = 30$

The next figure will have 30 acute angles.

Pattern in the Numbers

Yes, there is a clear pattern in the number of acute angles.

The sequence of the number of acute angles is: 3, 12, 21, 30, ...

This is an arithmetic progression. The first term is 3, and each subsequent term is found by adding a constant number, which is 9.

- $3 + 9 = 12$

- $12 + 9 = 21$

- $21 + 9 = 30$

So, the pattern is that each new figure in the sequence adds 9 acute angles to the previous one.

Intext Question (Page 34)

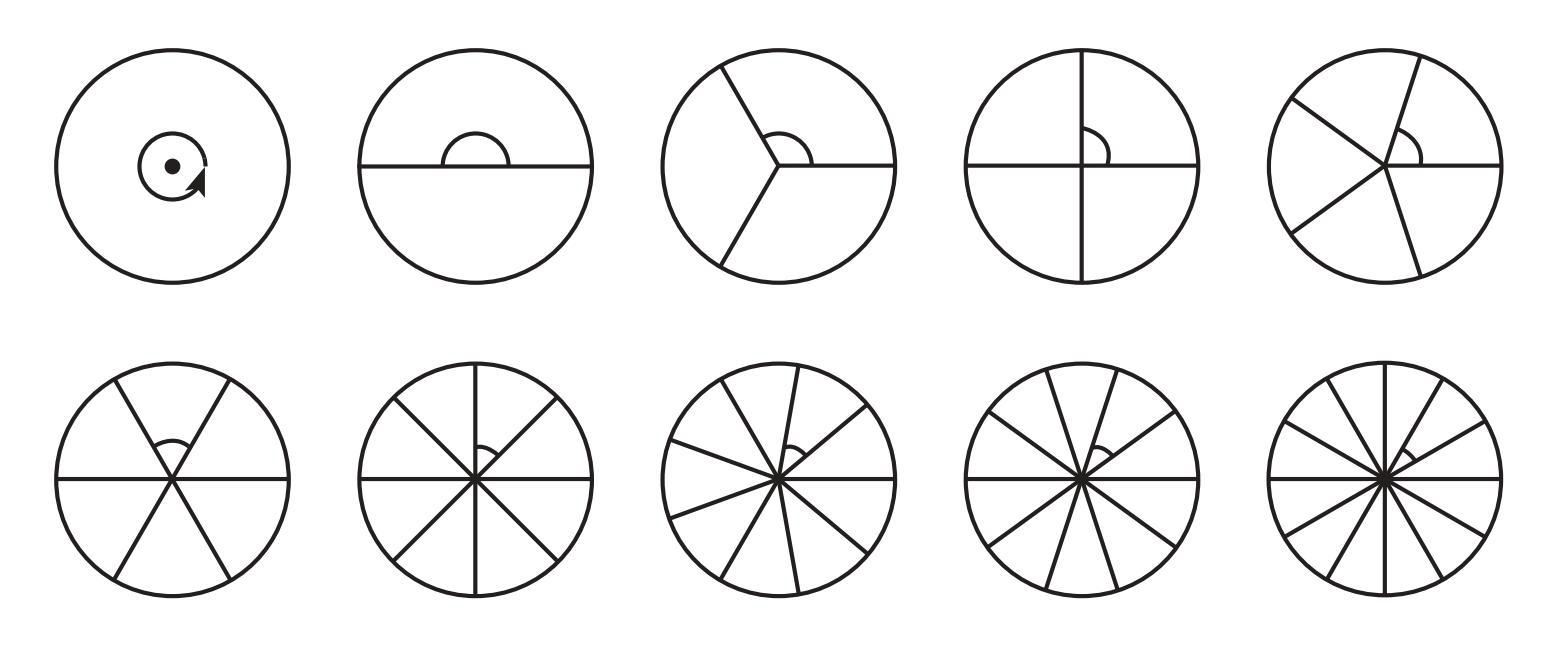

Answer:

The degree measure of the angle formed by dividing a circle into equal parts can be calculated using the fact that a complete circle represents a full turn, which is equal to $360^\circ$.

The formula to find the measure of the angle for each part is:

Angle = $\frac{\text{Total degrees in a circle}}{\text{Number of equal parts}} = \frac{360^\circ}{n}$

where 'n' is the number of parts the circle is divided into.

Using this formula, we can calculate the degree measure for each of the given circles:

| Number of Parts (n) | Calculation | Degree Measure of the Angle | Type of Angle |

| 1 | $\frac{360^\circ}{1}$ | $360^\circ$ | Complete Angle |

| 2 | $\frac{360^\circ}{2}$ | $180^\circ$ | Straight Angle |

| 3 | $\frac{360^\circ}{3}$ | $120^\circ$ | Obtuse Angle |

| 4 | $\frac{360^\circ}{4}$ | $90^\circ$ | Right Angle |

| 5 | $\frac{360^\circ}{5}$ | $72^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| 6 | $\frac{360^\circ}{6}$ | $60^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| 8 | $\frac{360^\circ}{8}$ | $45^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| 9 | $\frac{360^\circ}{9}$ | $40^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| 10 | $\frac{360^\circ}{10}$ | $36^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| 12 | $\frac{360^\circ}{12}$ | $30^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

The image below shows where these calculated degree measures should be written for each circle.

Figure it out (Page 35)

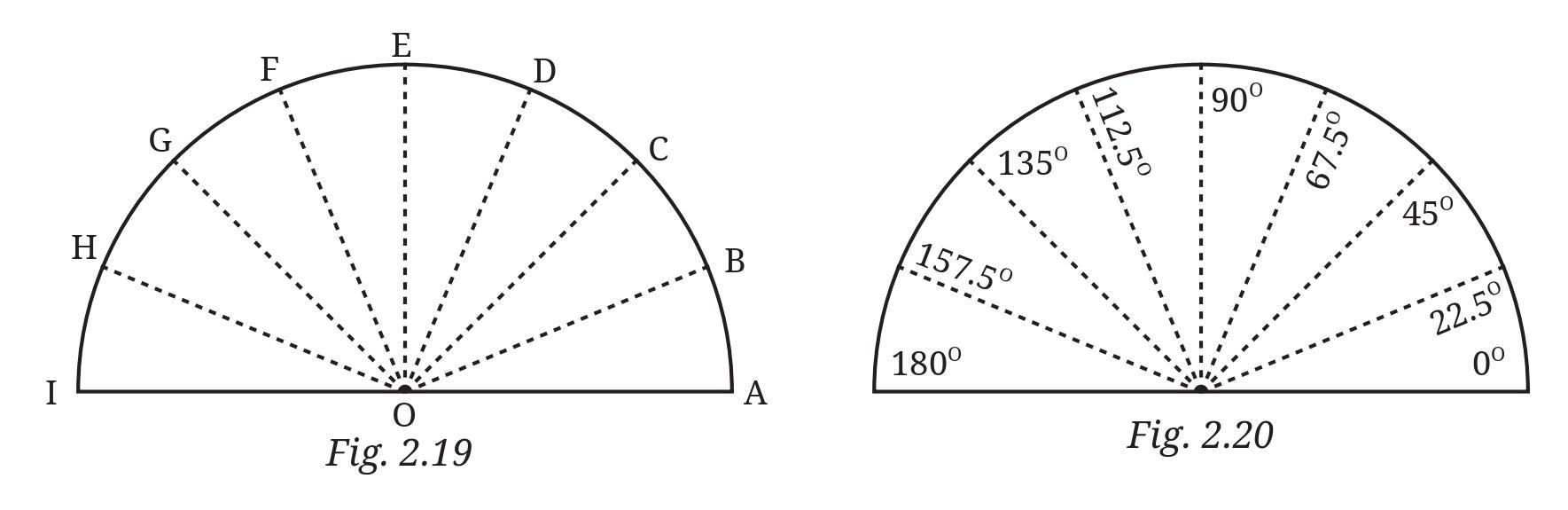

a. ∠ KAL

Notice that the vertex of this angle coincides with the centre of the protractor. So the number of units of 1 degree angle between KA and AL gives the measure of ∠KAL. By counting, we get

∠KAL = 30°.

Making use of the medium sized and large sized marks, is it possible to count the number of units in 5s or 10s?

b. ∠WAL

c. ∠TAK

Answer:

To find the measure of the angles, we will use the degree readings for each ray as specified. The measure of the angle between two rays is the absolute difference of their degree readings on the protractor.

The given degree readings for the rays originating from vertex A are:

- Ray AK: $50^\circ$

- Ray AL: $80^\circ$

- Ray AW: $130^\circ$

- Ray AT: $170^\circ$

a. ∠KAL

The measure of $∠KAL$ is the difference between the readings for ray AL and ray AK.

$∠KAL = \text{Reading of AL} - \text{Reading of AK}$

$∠KAL = 80^\circ - 50^\circ$

$∠KAL = 30^\circ$

Regarding the sub-question: Yes, it is possible to count the number of units in 5s or 10s. Protractors have large marks for every $10^\circ$ and medium-sized marks for every $5^\circ$. This design allows for a much faster reading of the angle compared to counting each one-degree mark individually.

b. ∠WAL

The measure of $∠WAL$ is the difference between the readings for ray AW and ray AL.

$∠WAL = \text{Reading of AW} - \text{Reading of AL}$

$∠WAL = 130^\circ - 80^\circ$

$∠WAL = 50^\circ$

c. ∠TAK

The measure of $∠TAK$ is the difference between the readings for ray AT and ray AK.

$∠TAK = \text{Reading of AT} - \text{Reading of AK}$

$∠TAK = 170^\circ - 50^\circ$

$∠TAK = 120^\circ$

Intext Question (Page 36)

Answer:

To find the measures of the different angles in the figure, we will use the outer scale of the protractor as requested. On this scale, the ray OU is the baseline at $0^\circ$.

The given degree readings for each ray on the outer scale are:

- Ray OU is at $0^\circ$.

- Ray OT is at $20^\circ$.

- Ray OS is at $55^\circ$.

- Ray OR is at $90^\circ$.

- Ray OQ is at $145^\circ$.

- Ray OP is at $180^\circ$.

The measure of an angle is the absolute difference between the readings of its two rays.

Here are the different angles that can be identified in the figure and their corresponding measures based on the provided readings:

| Angle Name | Calculation | Measure | Type of Angle |

| ∠UOT | $20^\circ - 0^\circ$ | $20^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| ∠UOS | $55^\circ - 0^\circ$ | $55^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| ∠UOR | $90^\circ - 0^\circ$ | $90^\circ$ | Right Angle |

| ∠UOQ | $145^\circ - 0^\circ$ | $145^\circ$ | Obtuse Angle |

| ∠UOP | $180^\circ - 0^\circ$ | $180^\circ$ | Straight Angle |

| ∠TOS | $55^\circ - 20^\circ$ | $35^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| ∠SOR | $90^\circ - 55^\circ$ | $35^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| ∠ROQ | $145^\circ - 90^\circ$ | $55^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| ∠QOP | $180^\circ - 145^\circ$ | $35^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| ∠TOR | $90^\circ - 20^\circ$ | $70^\circ$ | Acute Angle |

| ∠SOQ | $145^\circ - 55^\circ$ | $90^\circ$ | Right Angle |

| ∠ROP | $180^\circ - 90^\circ$ | $90^\circ$ | Right Angle |

| ∠TOQ | $145^\circ - 20^\circ$ | $125^\circ$ | Obtuse Angle |

| ∠SOP | $180^\circ - 55^\circ$ | $125^\circ$ | Obtuse Angle |

Intext Question (Page 39 - 40)

Question:

Think !

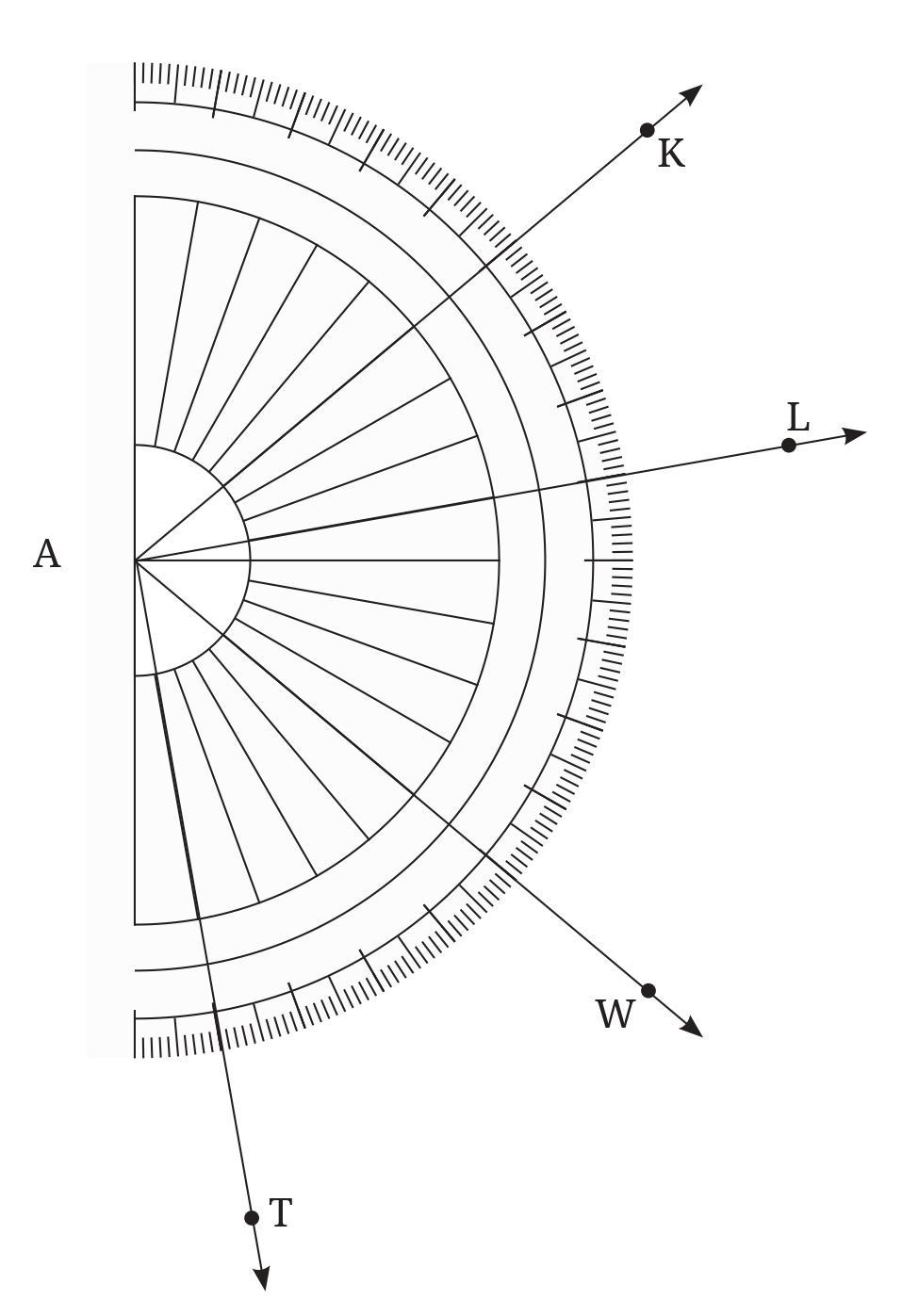

In Fig. 2.20, we have ∠AOB = ∠BOC = ∠COD = ∠DOE = ∠EOF = ∠FOG = ∠GOH = ∠HOI=_____. Why?

Answer:

To find the measure of each angle in Fig. 2.19, we need to analyze the structure of the figure. The figure shows a semicircle with diameter AI. A semicircle represents a straight angle, which measures a total of $180^\circ$.

The arc of the semicircle from A to I is divided into 8 equal segments by the points B, C, D, E, F, G, and H. These points create 8 equal angles at the center O.

To find the measure of one of these equal angles, we divide the total angle of the semicircle by the number of equal parts:

Measure of each angle = $\frac{\text{Total angle of a semicircle}}{\text{Number of equal parts}}$

Measure of each angle = $\frac{180^\circ}{8} = 22.5^\circ$

This result is also confirmed by looking at Fig. 2.20, where the first angle from the baseline ($0^\circ$) is marked as $22.5^\circ$.

Therefore, we can fill in the blank as follows:

In Fig. 2.20, we have ∠AOB = ∠BOC = ∠COD = ∠DOE = ∠EOF = ∠FOG = ∠GOH = ∠HOI = $22.5^\circ$.

Why?

The reason all these angles are equal is that the semicircle, which has a total central angle of $180^\circ$, has been divided into 8 equal parts. Since the arc is divided into equal segments (arc AB = arc BC = arc CD, and so on), the central angles subtended by these equal arcs are also equal. Therefore, the total $180^\circ$ angle is distributed equally among the 8 smaller angles.

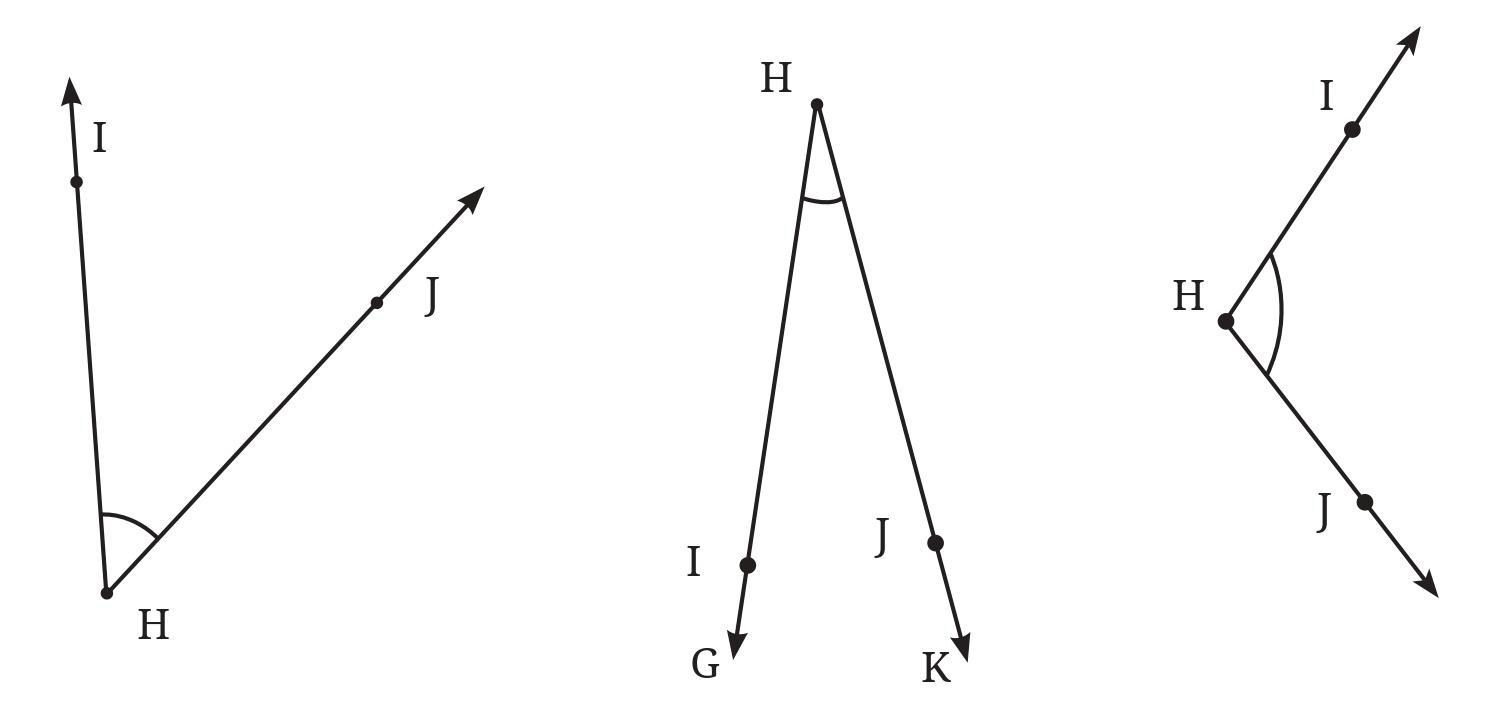

Figure it Out (Page 40 - 43)

Answer:

You are right to ask for a more careful observation. The degree measures of the angles are found by using a protractor. The following are the approximate measures obtained by carefully measuring each angle from the figures provided.

Angle 1 (Left)

The angle is named ∠IHJ.

Upon measuring with a protractor, its measure is found to be approximately 45°.

Since the measure is less than 90°, it is an acute angle.

Angle 2 (Middle)

The angle is named ∠GHK (or ∠IHJ).

Upon measuring with a protractor, its measure is found to be approximately 25°.

Since the measure is less than 90°, it is an acute angle.

Angle 3 (Right)

The angle is named ∠IHJ.

Upon measuring with a protractor, its measure is found to be approximately 110°.

Since the measure is greater than 90°, it is an obtuse angle.

Answer:

Measuring different angles in a classroom with a protractor reveals a variety of angle types. While many angles in the room's structure are right angles, other objects provide examples of acute and obtuse angles.

Here are the degree measures of angles found on some common classroom objects:

1. Corners of a Book, Desk, or Blackboard

Most books, desks, and blackboards are rectangular in shape. When you place a protractor at any of the four corners, you will find that the angle is a right angle.

The measure of the angle is $90^\circ$.

2. Angles of a Set Square (from a geometry box)

A standard geometry box contains two types of triangular set squares. Each set square has three angles with different measures:

a) The Isosceles Set Square: This set square has one right angle and two equal acute angles.

- The angles measure $45^\circ$, $45^\circ$, and $90^\circ$.

b) The Scalene Set Square: This set square has one right angle and two different acute angles.

- The angles measure $30^\circ$, $60^\circ$, and $90^\circ$.

3. Angle between the Blades of a Pair of Scissors

The angle between the blades of a pair of scissors is not fixed; it changes as you open or close them. This allows it to form different types of angles:

- When slightly open, it forms an acute angle (e.g., $30^\circ$ or $45^\circ$).

- When opened wider, it can form a right angle ($90^\circ$).

- When opened very wide, it forms an obtuse angle (e.g., $120^\circ$ or $135^\circ$).

4. Angle between the Hands of a Clock

The angle between the minute hand and the hour hand of a wall clock is constantly changing. Using a protractor, you can measure these angles at different times:

- At 3:00, the angle is a right angle, measuring $90^\circ$.

- At 1:00, the angle is an acute angle, measuring $30^\circ$.

- At 4:00, the angle is an obtuse angle, measuring $120^\circ$.

- At 6:00, the angle is a straight angle, measuring $180^\circ$.

Answer:

The angles shown are the interior angles and can be measured directly with a standard paper protractor.

Measurement for the First Angle (Left Figure)

The angle shown in the left figure, $∠IHJ$, is an acute angle. Upon careful measurement, its measure is indeed found to be approximately $40^\circ$.

Measurement for the Second Angle (Right Figure)

The angle shown in the right figure, also named $∠IHJ$, is an obtuse angle, as its measure is clearly greater than $90^\circ$.

Using a protractor, the measure of this angle is found to be approximately $115^\circ$.

Can a paper protractor be used here?

Yes, a standard paper protractor can be used here. It is the perfect tool for measuring both the acute angle ($40^\circ$) and the obtuse angle ($130^\circ$) directly, as both measures fall within the $0^\circ$ to $180^\circ$ range of a protractor.

Answer:

The angle shown in the figure is a reflex angle. A reflex angle is an angle that is greater than $180^\circ$ but less than $360^\circ$.

A standard protractor typically measures angles up to $180^\circ$, so it cannot be used to measure a reflex angle directly. However, we can find its measure indirectly by following a simple two-step process.

Step 1: Measure the Interior Angle

First, we need to measure the angle that is inside the vertex. This is the obtuse angle that is supplementary to the reflex angle. To do this:

1. Place the center of your protractor on the vertex of the angle.

2. Align the baseline ($0^\circ$ mark) of the protractor with one of the rays of the angle.

3. Read the degree measure where the second ray crosses the protractor's scale.

By measuring this interior angle, we find its value is approximately $100^\circ$.

Step 2: Subtract the Interior Angle from 360°

The total angle around a point (a full circle) is $360^\circ$. To find the measure of the reflex angle, we subtract the measure of the interior angle from $360^\circ$.

The formula is:

$Reflex\ Angle = 360^\circ - Interior\ Angle$

Now, we substitute the value we measured in Step 1:

$Reflex\ Angle = 360^\circ - 100^\circ$

$Reflex\ Angle = 260^\circ$

Therefore, the degree measure of the given reflex angle is approximately $260^\circ$.

Answer:

a.

This is an acute angle. Upon careful measurement, its degree measure is approximately $80^\circ$.

b.

This is an obtuse angle. Upon careful measurement, its degree measure is approximately $120^\circ$.

c.

This is an acute angle. It appears to be exactly half of a right angle. Its degree measure is approximately $60^\circ$.

d.

This is an obtuse angle. It appears to be a right angle ($90^\circ$) plus an acute angle of $45^\circ$. Its degree measure is approximately $130^\circ$.

e.

This is an obtuse angle. Its degree measure is approximately $128^\circ$.

f.

This is an acute angle. It appears to be the angle of an equilateral triangle. Its degree measure is approximately $60^\circ$.

Answer:

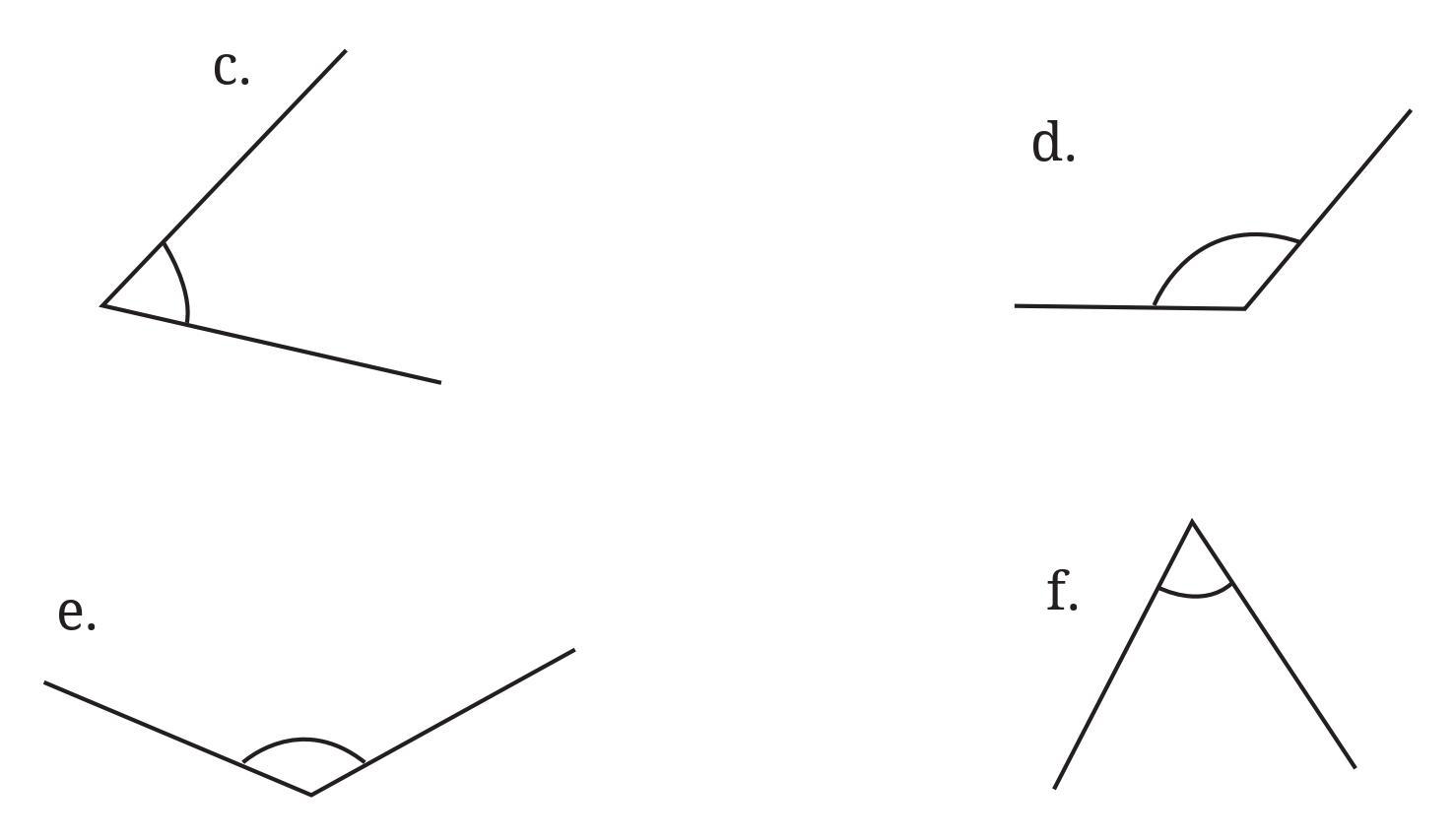

To find the degree measures of the angles, we will use the specific readings provided from the outer scale of the protractor. The measure of an angle is the absolute difference between the readings of the two rays that form it.

The given readings on the outer scale, with ray XA as the baseline at $0^\circ$, are:

- Ray XA is at $0^\circ$.

- Ray XB is at $65^\circ$.

- Ray XC is at $95^\circ$.

- Ray XE is at $180^\circ$.

Measure of ∠BXE

This angle is formed by the rays XB and XE. Its measure is the difference between their readings on the outer scale.

$∠BXE = \text{Reading of XE} - \text{Reading of XB}$

$∠BXE = 180^\circ - 65^\circ = 115^\circ$

Therefore, the measure of ∠BXE is $115^\circ$.

Measure of ∠CXE

This angle is formed by the rays XC and XE. Its measure is the difference between their readings on the outer scale.

$∠CXE = \text{Reading of XE} - \text{Reading of XC}$

$∠CXE = 180^\circ - 95^\circ = 85^\circ$

Therefore, the measure of ∠CXE is $85^\circ$.

Measure of ∠AXB

This angle is formed by the rays XA and XB. Its measure is the reading for ray XB, as the baseline ray XA is at $0^\circ$.

$∠AXB = \text{Reading of XB} - \text{Reading of XA}$

$∠AXB = 65^\circ - 0^\circ = 65^\circ$

Therefore, the measure of ∠AXB is $65^\circ$.

Measure of ∠BXC

This angle is formed by the rays XB and XC. Its measure is the difference between their readings on the outer scale.

$∠BXC = \text{Reading of XC} - \text{Reading of XB}$

$∠BXC = 95^\circ - 65^\circ = 30^\circ$

Therefore, the measure of ∠BXC is $30^\circ$.

Answer:

From the figure, we have four rays QP, QR, QS, and QT originating from a common point Q.

The ray QP is taken as the reference or baseline, representing $0^\circ$.

The angles formed by other rays with respect to the ray QP are given as:

The angle formed by ray QR with ray QP is $45^\circ$.

The angle formed by ray QS with ray QP is $100^\circ$.

The angle formed by ray QT with ray QP is $150^\circ$.

To Find:

The degree measures of $\angle$PQR, $\angle$PQS, and $\angle$PQT.

Solution:

We are asked to find the measures of the angles starting from the ray QP to the rays QR, QS, and QT respectively. These values are directly provided in the question's context.

1. Measure of $\angle$PQR:

This is the angle formed by the rays QP and QR. Based on the given information, the measure of this angle is $45^\circ$.

So, $\angle$PQR = $45^\circ$.

2. Measure of $\angle$PQS:

This is the angle formed by the rays QP and QS. Based on the given information, the measure of this angle is $100^\circ$.

So, $\angle$PQS = $100^\circ$.

3. Measure of $\angle$PQT:

This is the angle formed by the rays QP and QT. Based on the given information, the measure of this angle is $150^\circ$.

So, $\angle$PQT = $150^\circ$.

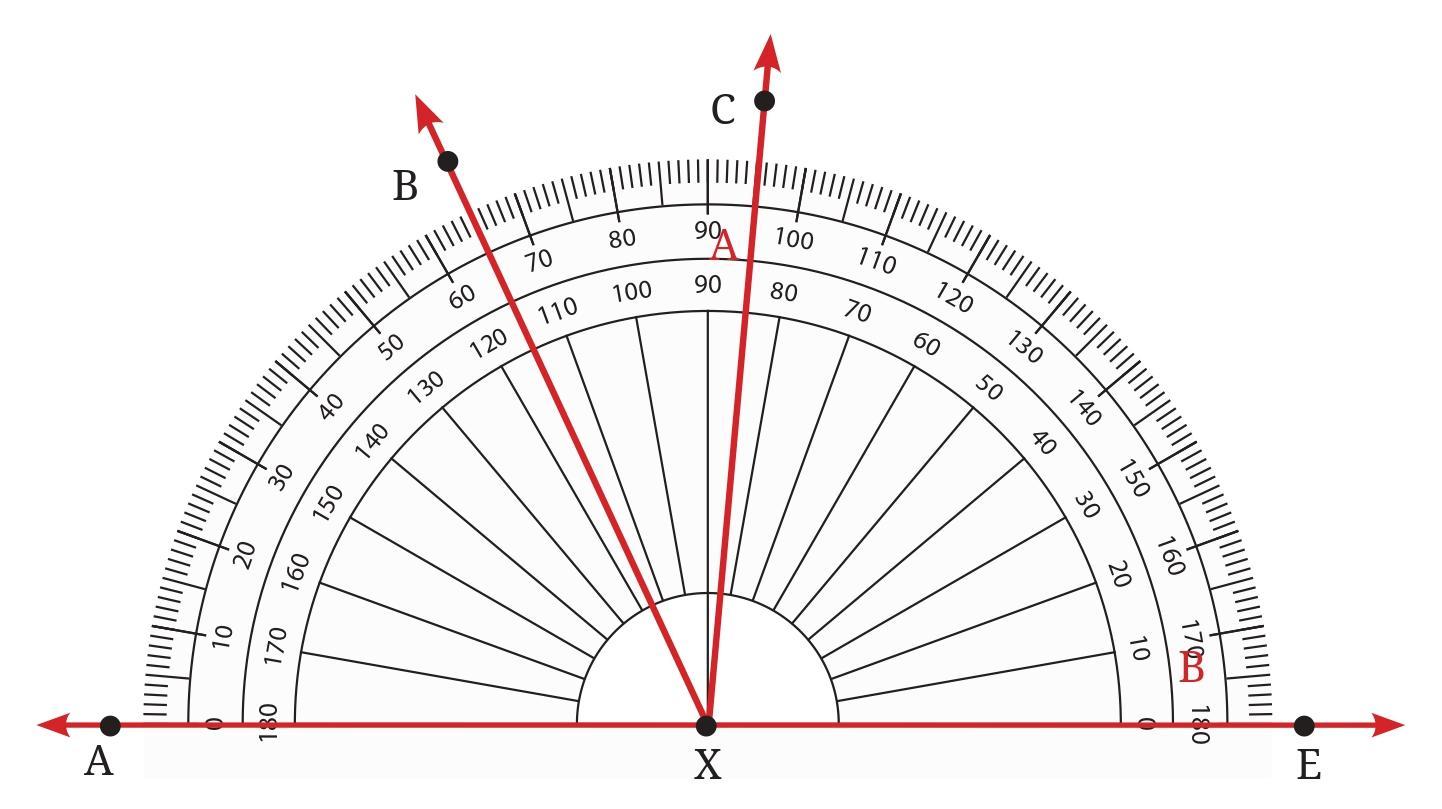

Answer:

A set of 8 visual instructions to create a paper rabbit face (origami) from a square piece of paper.

To Do:

This is a practical, activity-based question. You need to perform the following steps:

1. Take a square sheet of paper.

2. Follow the folding instructions from step 1 to step 8 as shown in the image to make the paper rabbit face.

3. After making the craft, carefully unfold the paper completely back into its original square shape.

4. You will see a pattern of creases on the paper. Use a pencil and a ruler to draw straight lines over all these creases.

5. Use a protractor to measure the different angles formed by the intersecting crease lines.

Expected Observations and Measurements:

After performing the activity and measuring the angles with a protractor, you will discover various angles formed by the creases. The angles you are most likely to find are:

1. Right Angles ($90^\circ$):

You will find several right angles. For example:

• The four corners of the original square paper are all $90^\circ$.

• The main diagonal creases will intersect at the center of the paper, forming four $90^\circ$ angles.

2. Acute Angles (less than $90^\circ$):

You will find multiple acute angles. The most common ones are:

• $45^\circ$: The very first fold along the diagonal (Step 1) divides the $90^\circ$ corner angles into two $45^\circ$ angles. You will find many $45^\circ$ angles where the creases meet the edges of the paper.

• $22.5^\circ$: Some of the more detailed folds, like those for the rabbit's ears (Steps 4, 5, 6), involve bisecting $45^\circ$ angles. This creates smaller angles measuring $22.5^\circ$.

3. Obtuse Angles (greater than $90^\circ$):

You might also find some obtuse angles, such as:

• $135^\circ$: These angles are often found next to $45^\circ$ angles. For example, if you look at a point on the edge of the paper where a $45^\circ$ crease meets it, the angle on the other side of the crease along the straight edge will be $180^\circ - 45^\circ = 135^\circ$. You can also find $135^\circ$ angles formed by the sum of a $90^\circ$ and a $45^\circ$ angle at the center.

By completing this activity, you will get hands-on experience in identifying and measuring different types of angles created through geometric folding.

Try it for other triangles as well, and then make a conjecture for what happens in general! We will come back to why this happens in a later year.

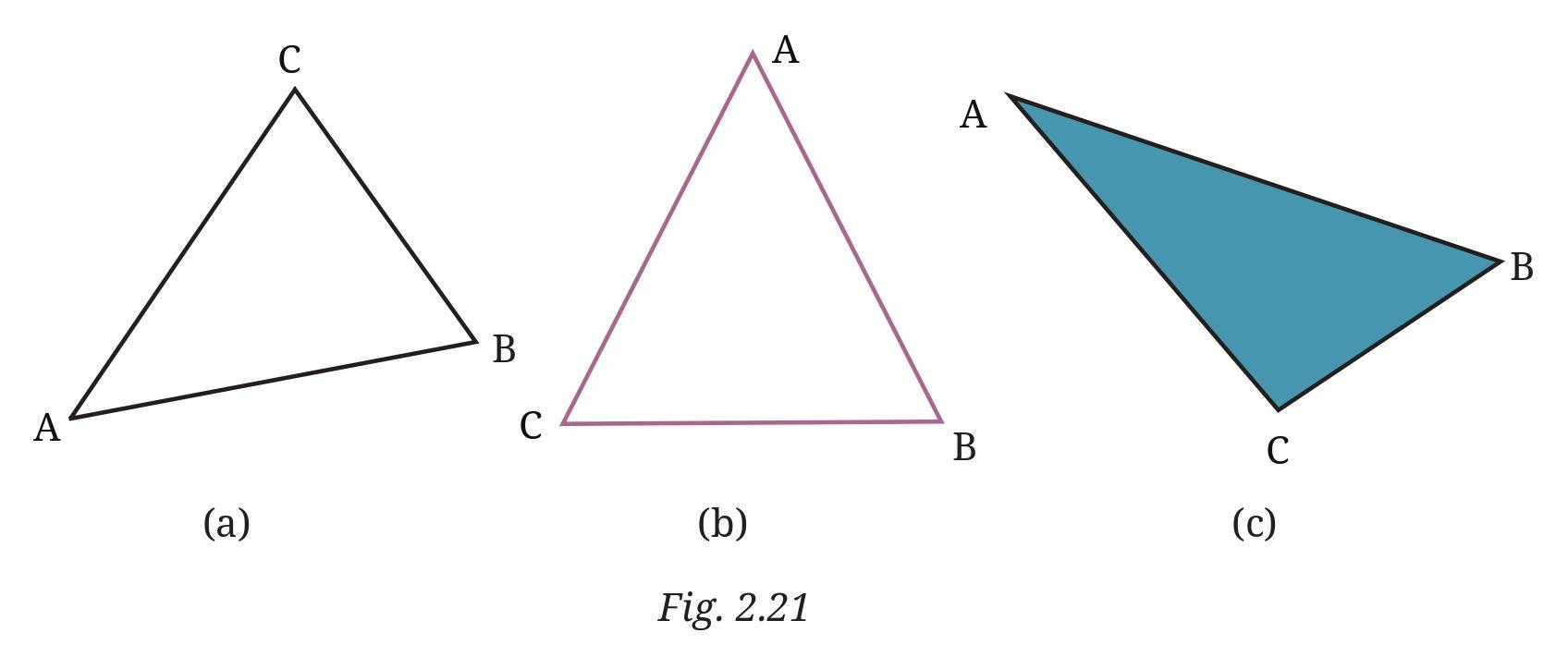

Answer:

This is a practical activity that requires a protractor. The steps to be followed are:

1. Take a protractor and place its center on the vertex A of the triangle in Fig. 2.21 (a). Align the baseline of the protractor with the side AB.

2. Measure the angle $\angle CAB$ (or $\angle A$). Similarly, measure $\angle ABC$ ($\angle B$) and $\angle BCA$ ($\angle C$).

3. Record the three angle measurements.

4. Add the three measurements together: $\angle A + \angle B + \angle C$.

5. Repeat steps 1-4 for the other two triangles shown in Fig. 2.21 (b) and Fig. 2.21 (c).

6. Observe the sum of the angles for all three triangles and form a general conclusion (a conjecture).

Solution and Observation:

Since we can only estimate visually, the following table provides more carefully considered approximations for the angles in each triangle. When you measure them with a protractor, you should get values very close to these.

| Triangle | Approximate Measure of $\angle A$ | Approximate Measure of $\angle B$ | Approximate Measure of $\angle C$ | Sum of Angles ($\angle A + \angle B + \angle C$) |

| Fig. 2.21 (a) | $45^\circ$ | $70^\circ$ | $65^\circ$ | $45^\circ + 70^\circ + 65^\circ = 180^\circ$ |

| Fig. 2.21 (b) | $54^\circ$ | $63^\circ$ | $63^\circ$ | $54^\circ + 63^\circ + 63^\circ = 180^\circ$ |

| Fig. 2.21 (c) | $30^\circ$ | $53^\circ$ | $97^\circ$ | $30^\circ + 53^\circ + 97^\circ = 180^\circ$ |

The crucial observation from your physical measurements will be that, despite the different shapes and sizes of the triangles, the sum of their three interior angles is consistently $180^\circ$. Any minor deviation (like $179^\circ$ or $181^\circ$) would be due to small errors in measurement, but the true sum is always exactly $180^\circ$.

Conjecture:

Based on the consistent results from your measurements, you can make the following conjecture:

The sum of the measures of the three interior angles of any triangle is always $180^\circ$.

This is a fundamental and proven theorem in geometry known as the Angle Sum Property of a Triangle.

For any triangle ABC, this property can be written as:

$\angle A + \angle B + \angle C = 180^\circ$

Figure it Out (Page 45 - 46)

a. The hands of a clock make different angles at different times. At 1 o’clock, the angle between the hands is 30°. Why?

b. What will be the angle at 2 o’clock? And at 4 o’clock? 6 o’clock?

c. Explore other angles made by the hands of a clock.

Answer:

The face of a clock is a complete circle, which has a total of $360^\circ$.

A clock face is divided into 12 equal parts, representing the hours.

Therefore, the angle between any two consecutive hour numbers (like between 12 and 1, or 1 and 2) is calculated as:

Angle per hour = $\frac{\text{Total angle in a circle}}{\text{Number of hours}} = \frac{360^\circ}{12} = 30^\circ$

So, for every hour, the hour hand moves by $30^\circ$. We will use this fundamental concept to answer the questions. This calculation is valid when the minute hand is exactly at 12.

a. The angle at 1 o’clock is 30°. Why?

At 1 o'clock (1:00), the minute hand is pointing exactly at the number 12, and the hour hand is pointing exactly at the number 1.

The gap between the hour hand and the minute hand is exactly one hour division.

As calculated above, the angle for one hour division is $30^\circ$.

Therefore, the angle between the hands at 1 o'clock is $1 \times 30^\circ = 30^\circ$.

b. What will be the angle at 2 o’clock? And at 4 o’clock? 6 o’clock?

We can find the angles for these times using the same logic.

At 2 o'clock (2:00):

The minute hand is at 12 and the hour hand is at 2. There are 2 hour divisions between them.

Angle = $2 \times 30^\circ = 60^\circ$.

At 4 o'clock (4:00):

The minute hand is at 12 and the hour hand is at 4. There are 4 hour divisions between them.

Angle = $4 \times 30^\circ = 120^\circ$.

At 6 o'clock (6:00):

The minute hand is at 12 and the hour hand is at 6. There are 6 hour divisions between them. The hands form a straight line.

Angle = $6 \times 30^\circ = 180^\circ$.

| Time | Hour Divisions Between Hands | Calculation | Angle |

| 2 o'clock | 2 | $2 \times 30^\circ$ | $60^\circ$ |

| 4 o'clock | 4 | $4 \times 30^\circ$ | $120^\circ$ |

| 6 o'clock | 6 | $6 \times 30^\circ$ | $180^\circ$ |

c. Explore other angles made by the hands of a clock.

We can explore angles at other times as well:

At 3 o'clock (3:00):

The minute hand is at 12 and the hour hand is at 3. The gap is 3 hour divisions.

Angle = $3 \times 30^\circ = 90^\circ$. This is a right angle.

At 9 o'clock (9:00):

The minute hand is at 12 and the hour hand is at 9. If we measure clockwise from 12 to 9, the gap is 9 hour divisions, giving an angle of $9 \times 30^\circ = 270^\circ$. This is called a reflex angle.

However, we usually consider the smaller angle between the hands. The gap from 9 back to 12 is 3 hour divisions.

Angle = $3 \times 30^\circ = 90^\circ$. This is also a right angle.

Is it possible to express the amount by which a door is opened using an angle? What will be the vertex of the angle and what will be the arms of the angle?

Answer:

Yes, it is absolutely possible to express the amount by which a door is opened using an angle. The opening of a door is a rotational movement around a fixed point, and the extent of this rotation is measured in degrees.

To understand this, we need to identify the components of the angle:

Vertex of the Angle:

The vertex of the angle is the point around which the rotation occurs. In the case of a door, the vertex is the axis of the hinges. When viewed from the top (as in the given illustration), this axis appears as a single point where the door pivots.

Arms of the Angle:

An angle is formed by two arms or rays originating from the vertex. For a door, the two arms are:

1. The initial position of the door: This is the line representing the door when it is fully closed, lying flat against the door frame.

2. The final position of the door: This is the line representing the door's position after it has been opened to a certain extent.

The angle is the measure of the opening between these two positions.

Examples:

• When the door is completely closed, the angle of opening is $0^\circ$.

• If the door is opened slightly, as shown in the picture, it forms an acute angle (an angle less than $90^\circ$).

• If the door is opened wide so that it is perpendicular to the wall, it forms a right angle, which is $90^\circ$.

• If the door could swing all the way around to be flat against the wall on the other side, it would form a straight angle, which is $180^\circ$.

Answer:

Yes, there is a very clear angle involved in the motion of a swing. The angle represents how far back the swing is pulled before it is let go.

To see the angle, we need to identify its three main parts: the vertex and the two arms.

Vertex of the Angle:

The vertex is the pivot point around which the swing moves. In this case, it is the point where the rope is tied to the tree branch.

Arms of the Angle:

The angle is formed by two imaginary lines (arms) that meet at the vertex.

1. The First Arm: This is the position of the swing when it is at rest, hanging straight down due to gravity. This is also called the vertical or equilibrium position.

2. The Second Arm: This is the position of the swing at its highest point, just as Vidya starts her motion. It is the line formed by the rope when she has pulled it back as far as she can.

The angle is the measure of the opening between the swing's starting position and its resting (vertical) position.

How the Angle Affects Speed:

Vidya's observation is correct. When she pulls the swing further back, she creates a larger starting angle. A larger angle means she starts from a higher position. When she lets go from a higher point, she has a longer path to "fall" towards the bottom of the swing, which makes her move faster. Therefore, a greater starting angle results in a greater speed at the lowest point of the swing.

Answer:

Yes, angles are the perfect way to describe the slopes of the slabs in this toy. The steepness of each ramp is determined by the angle it makes with a horizontal line.

What are the arms of each angle?

For each slanting slab, the angle describing its slope is formed by two arms:

1. The First Arm: The surface of the slanting slab itself. This is the path the marble rolls down.

2. The Second Arm: An imaginary horizontal line that starts from the higher end of the slab and extends outwards, parallel to the ground.

Which arm is visible and which is not?

• Visible Arm: The slanting slab is the visible arm. You can see it as part of the toy's structure.

• Invisible Arm: The imaginary horizontal line is the arm that is not visible. It is a reference line that we use to measure the angle of the slope.

The observation in the question is correct: the larger the angle between the slab and the imaginary horizontal line, the steeper the slope, and the faster the marbles will roll down due to the increased effect of gravity.

Hint: Observe the horizontal line touching the insects.

Answer:

Yes, angles are the standard way to describe the amount of rotation of any object. Rotation is essentially a "turn," and an angle measures exactly how much of a turn has been made.

How can angles describe the rotation?

An angle measures the difference between an object's starting direction and its ending direction after a turn. For example, if an insect is facing forward and then turns to face right, it has made a $90^\circ$ turn.

What are the vertex and the arms of the angle?

To measure the rotation, we define the angle as follows:

Vertex:

The vertex is the center point of the rotation. For the insects, this would be an imaginary point in the middle of their body around which they are turning.

Arms:

The arms are used to measure the amount of turn from the starting position.

1. The First Arm (Initial Position): This is a reference line drawn from the center of the insect (the vertex) in its starting direction. In the image, the first snail and the first ladybug are both aligned with the horizontal line, so we can consider the horizontal line pointing to the right as our first arm.

2. The Second Arm (Final Position): This is the same reference line after the insect has rotated to its new position. For the second snail and ladybug, this would be a line drawn from their center in the new direction they are facing.

Applying this to the images:

The Snail:

The first snail is facing horizontally to the right (let's call this the $0^\circ$ position). The second snail is facing almost straight up. It has rotated counter-clockwise. The angle of rotation is the angle between the horizontal line and the new upward-facing direction, which is approximately a $90^\circ$ turn.

The Ladybug:

Similarly, the first ladybug is facing horizontally to the right. The second ladybug is facing straight up. It has also made a counter-clockwise rotation of exactly $90^\circ$ (a right angle).

Figure it Out (Page 49 - 50)

Answer:

This is a complete activity where we will identify all the angles at points A, C, P, L, R, and S, use the provided measurements, and then make important observations based on the results.

1. Identifying and Measuring the Angles

At each point where a transversal (the slanted line) crosses one of the parallel lines (the horizontal lines), four angles are formed. These consist of two identical small (acute) angles and two identical big (obtuse) angles. The table below shows the measured values for all these angles.

| Point | Angle Type | Number of such angles at the point | Measurement |

| A | Acute (Small) | 2 | $70^\circ$ |

| Obtuse (Big) | 2 | $110^\circ$ | |

| C | Acute (Small) | 2 | $70^\circ$ |

| Obtuse (Big) | 2 | $110^\circ$ | |

| P | Acute (Small) | 2 | $85^\circ$ |

| Obtuse (Big) | 2 | $95^\circ$ | |

| L | Acute (Small) | 2 | $85^\circ$ |

| Obtuse (Big) | 2 | $95^\circ$ | |

| R | Acute (Small) | 2 | $75^\circ$ |

| Obtuse (Big) | 2 | $105^\circ$ | |

| S | Acute (Small) | 2 | $75^\circ$ |

| Obtuse (Big) | 2 | $105^\circ$ |

2. Observations After Measuring

By analyzing the measured values in the table, we can discover several important geometric rules.

Observation 1: At any single intersection point, the big and small angles add up to $180^\circ$.

This is because they form a straight line (a linear pair). For example:

- At point P: $85^\circ$ (Acute) + $95^\circ$ (Obtuse) = $180^\circ$.

- At point R: $75^\circ$ (Acute) + $105^\circ$ (Obtuse) = $180^\circ$.

- At point A: $70^\circ$ (Acute) + $110^\circ$ (Obtuse) = $180^\circ$.

Observation 2: The angles at the top parallel line are identical to the angles at the bottom parallel line for the same transversal.

The parallel nature of the lines causes the angles to be replicated at each intersection.

- For transversal AC: The angles at A ($70^\circ, 110^\circ$) are exactly the same as the angles at C ($70^\circ, 110^\circ$).

- For transversal PL: The angles at P ($85^\circ, 95^\circ$) are exactly the same as the angles at L ($85^\circ, 95^\circ$).

- For transversal RS: The angles at R ($75^\circ, 105^\circ$) are exactly the same as the angles at S ($75^\circ, 105^\circ$).

Observation 3: Interior angles on the same side of a transversal add up to $180^\circ$.

If we look at the angles that are "inside" the two parallel lines, the ones on the same side of the transversal are supplementary.

- For transversal AC, the interior angle at A is $110^\circ$ and the interior angle at C is $70^\circ$. Their sum is: $110^\circ + 70^\circ = 180^\circ$.

This activity shows that there are predictable and consistent rules for angles formed when lines intersect, especially when parallel lines are involved.

a. 110°

b. 40°

c. 75°

d. 112°

e. 134°

Answer:

This is a practical drawing exercise. To complete it, you will need a pencil, a ruler (straight edge), and a protractor.

General Steps to Draw an Angle Using a Protractor:

Step 1: Draw a Base Ray

Use your ruler to draw a straight horizontal line on your paper. This will be the first arm of your angle. Mark a point 'O' on one end (this will be the vertex) and another point 'A' on the line. This gives you the ray OA.

Step 2: Place the Protractor

Take your protractor and place its center point exactly on the vertex 'O'. Carefully align the baseline of the protractor (the line that reads 0° and 180°) with your ray OA.

Step 3: Find and Mark the Angle

Look at the scale on the protractor that starts with 0° along your ray OA. Follow this scale around until you find the desired angle measurement. Make a small dot or mark at that point. Let's call this mark 'B'.

Step 4: Draw the Second Ray

Remove the protractor. Use your ruler to draw a straight line connecting the vertex 'O' to the point 'B' that you just marked.

The angle formed, $\angle AOB$, is the angle you wanted to draw.

Drawing the Specific Angles:

a. To draw an angle of 110° (Obtuse Angle)

Follow the steps above. After placing the protractor, find the 110° mark and place your dot. Join it to the vertex O. The resulting angle is $\angle AOB = 110^\circ$.

b. To draw an angle of 40° (Acute Angle)

Follow the steps above. Find the 40° mark on the protractor's scale and make a dot. Join the dot to the vertex O. The resulting angle is $\angle AOB = 40^\circ$.

c. To draw an angle of 75° (Acute Angle)

Follow the steps above. Find the 75° mark (it will be halfway between 70° and 80°) and make a dot. Join the dot to the vertex O. The resulting angle is $\angle AOB = 75^\circ$.

d. To draw an angle of 112° (Obtuse Angle)

Follow the steps above. Find the 112° mark (two small tick marks past 110°) and make a dot. Join the dot to the vertex O. The resulting angle is $\angle AOB = 112^\circ$.

e. To draw an angle of 134° (Obtuse Angle)

Follow the steps above. Find the 134° mark (four small tick marks past 130°) and make a dot. Join the dot to the vertex O. The resulting angle is $\angle AOB = 134^\circ$.

Also, write down the steps you followed to draw the angle.

Answer:

To draw an angle that is the same size as the one given, we first need to measure the given angle using a protractor and then draw a new angle with that exact measurement. Here are the detailed steps.

Step 1: Measure the Given Angle ($\angle IHJ$)

First, we must find the degree measure of the angle shown in the figure.

1. Identify the vertex of the angle, which is point H.

2. Take your protractor and place its center point directly on the vertex H.

3. Align the baseline (the 0° line) of the protractor with one of the arms of the angle, for example, the ray HJ.

4. Look at the scale on the protractor and read the degree measure where the other arm, ray HI, crosses the scale.

Upon measuring, you will find that the measure of the angle is 115°.

Step 2: Draw a New Angle of 115°

Now that we know the measurement is 115°, we can draw a new angle with the same size. Let's call our new angle $\angle AOB$.

a. Draw a Base Ray:

Use a ruler to draw a straight line on your paper. Mark a point O at one end to be the vertex and another point A on the line. This gives you the ray OA.

b. Place the Protractor:

Place the center of your protractor on the vertex O. Align the baseline of the protractor (the 0° line) with the ray OA.

c. Mark the Angle:

Find the 115° mark on the protractor's scale (starting from 0° on the side of your ray). Make a small dot at this mark with your pencil. Let's call this point B.

d. Draw the Second Ray:

Remove the protractor. Use your ruler to draw a straight line from the vertex O to the point B.

The resulting angle, $\angle AOB$, has a measure of 115°, which is the same as the given angle $\angle IHJ$.

Figure it Out (Page 51 - 52)

a. An acute angle

b. An obtuse angle

c. A reflex angle

Mark the intended angles with curves to specify the angles. One has been done for you.

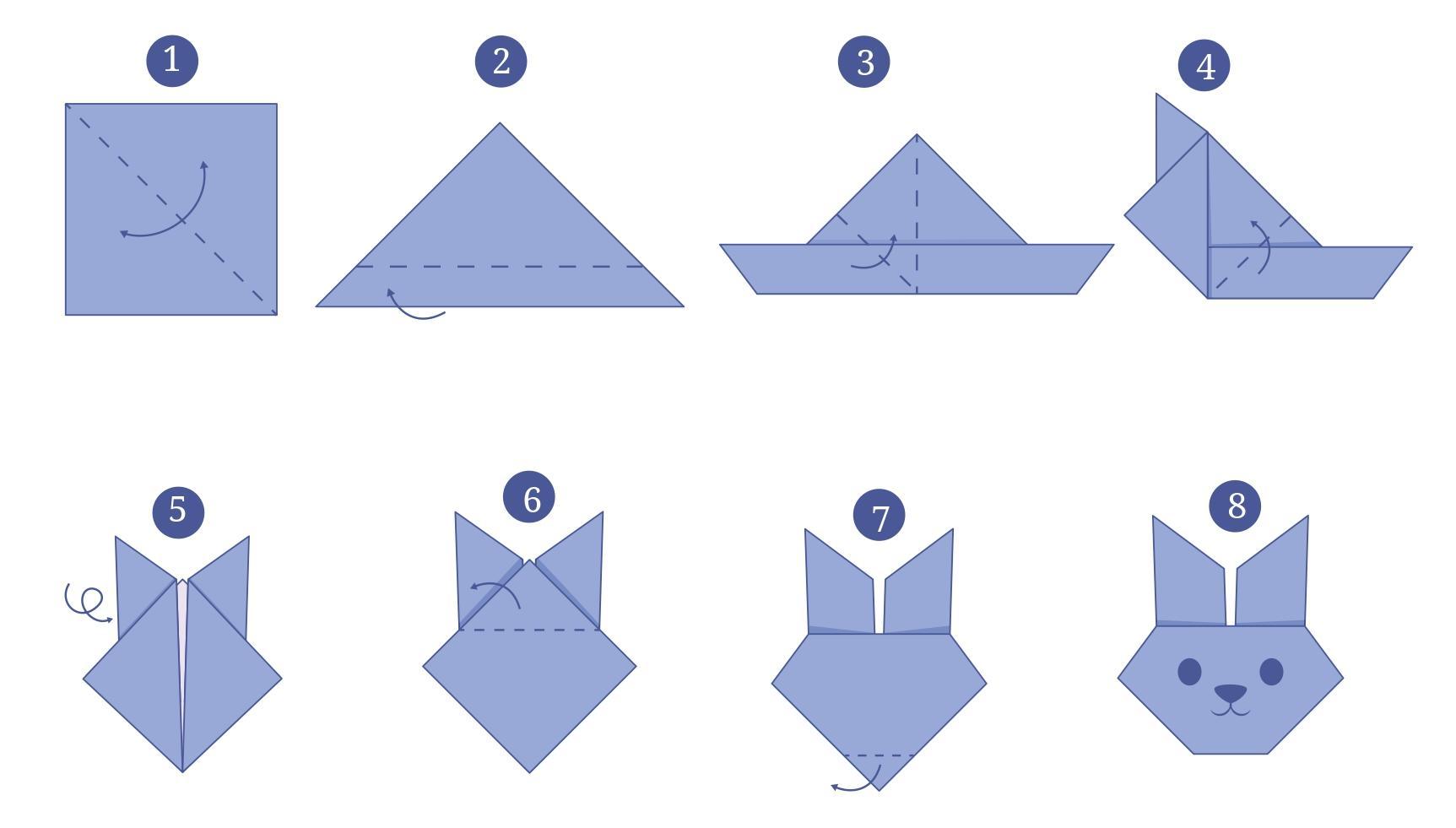

Answer:

In this exercise, we will use a dot grid to draw different types of angles by connecting points. For each part, we start with a given red line segment and add another line segment from one of its endpoints (the vertex) to another dot on the grid.

a. An Acute Angle

An acute angle is an angle that measures less than 90° (a right angle).

To draw an acute angle, we start with the given horizontal line. Choosing the left endpoint as the vertex, we draw a second line to a dot that is slightly upwards. The resulting angle is clearly smaller than a corner of a square, making it acute.

b. An Obtuse Angle

An obtuse angle is an angle that measures more than 90° but less than 180° (a straight line).

To draw an obtuse angle, we start with the horizontal line. From the left endpoint (our vertex), we draw a second line that opens wider than a right angle. A line going straight up would be 90°, so we draw a line going up and to the left.

c. A Reflex Angle

A reflex angle is an angle that measures more than 180° but less than 360° (a full circle). It is the larger angle on the outside of a standard angle.

To show a reflex angle, we start with the given diagonal line. From the top-left endpoint, we draw a second line (for example, a horizontal line to the right). This creates a standard obtuse angle on the inside. The reflex angle is the much larger angle that goes around the "outside" of the vertex. We mark this larger path with a big curve.

a. ∠PTR

b. ∠PTQ

c. ∠PTW

d. ∠WTP

Answer:

To solve this, we will use the given degree measures to calculate each specified angle. After finding the measurement, we will classify the angle based on the following definitions:

- An Acute Angle is greater than 0° and less than 90°.

- A Right Angle is exactly 90°.

- An Obtuse Angle is greater than 90° and less than 180°.

- A Reflex Angle is greater than 180° and less than 360°.

The measurement of the angles from the baseline ray TW are:

$\angle WTQ = 45^\circ$

$\angle WTR = 75^\circ$

$\angle WTP = 105^\circ$

a. ∠PTR

This angle is the difference between the measure of $\angle WTP$ and $\angle WTR$.

$\angle PTR = \angle WTP - \angle WTR$

$\angle PTR = 105^\circ - 75^\circ = 30^\circ$

Since $0^\circ < 30^\circ < 90^\circ$, it is an acute angle.

b. ∠PTQ

This angle is the difference between the measure of $\angle WTP$ and $\angle WTQ$.

$\angle PTQ = \angle WTP - \angle WTQ$